SSL could avoid supervised learning

For select supervised tasks with SSL models satisfying certain properties

Figure 1. Named entity recognition (NER) is solved in this post with self-supervised learning (SSL) alone avoiding supervised learning. The approach described here addresses the challenges facing any NER model in real-world applications. A supervised model, in particular, requires sufficient labeled sentences to address the cases illustrated in this figure : - (a) terms whose entity types change based on sentence context (b) sentences with very little context to determine entity type (c) terms whose casing offers cue to the entity type (d) entity type of complete or proper subsets of phrase spans (e) sentences where multiple entity types are possible in a sentence position and only the word in that position offers a clue to the entity type (f) a single term that has different meanings in different contexts (g) detecting numerical elements and units (h) recognizing entity types spanning different domains, that need to be recognized for a use case(e.g. biomedical use of detecting biomedical terms as well as patient identities/health information). Image by Author

TL;DR

Self-supervised learning (SSL) could be used to avoid supervised learning for some tasks leveraging self-supervised models like BERT, as is, without fine-tuning (supervision). For instance, this post describes an approach to perform named-entity recognition without fine-tuning a model on sentences. Instead, a small subset of BERT’s learned vocabulary is manually labeled and the labeled subset strength is magnified over 1k-30k times with clustering in vocabulary vector space. This magnified set is used to perform NER using BERT’s fill mask capability. The approach is used to label 69 entity types that fall into 17 broad entity groups spanning two domains - biomedical (disease, drug, genes, etc. ) and patient information (person, location, organization, etc.).

Introduction

Self-supervised learning (SSL) is increasingly used to solve language and vision tasks that are traditionally solved with supervised learning.

SSL has been the predominant approach to date in state-of-art approaches for ascribing labels to either whole or parts of an input. The labels in many cases are synthetic in nature - that is they are extraneous to the input and this necessitates training a model on (input, label) pairs to learn the mapping from input to the synthetic label. Examples of this in NLP are, ascribing labels like noun, verb, etc. to words in a sentence (POS tagging), ascribing a label that describes the type of relationship between two phrases in a sentence (relation extraction) or ascribing a label to a sentence (e.g. sentiment analysis - positive, negative, neutral, etc.).

SSL could be leveraged to avoid supervised learning for certain labeling tasks if an SSL model has the following properties

- the pretext task is predicting missing/corrupted portions of the input

- any input to the model is represented by a fixed set of learned representations, which we will refer to as input vector space.

- the vector space of the model output, output vector space, is the same as the input vector space. This property is a natural consequence of the pretext task predicting (representations of) missing/corrupted portions of the input

Given such an SSL model, any task that involves labeling individual parts of an input (e.g. named entity recognition) is a potential candidate for solving using just the SSL model.

This post uses SSL models, satisfying the above properties, to perform named entity recognition (NER) without the need for supervised learning.

NER - the task of identifying the entity type for a word or phrase in a sentence, is typically done to date by training a model on sentences manually labeled with entity types for words/phrases occurring in the sentence.

For example, in the sentence below, we want a trained model to label Lou Gehrig as Person, XCorp as Organization, New York as Location, and Parkinson’s as Disease.

Lou Gehrig [PERSON] who works for XCorp [ORGANIZATION] and lives in New York [LOCATION] suffers from Parkinson’s [DISEASE]

The SSL based approach described in this post, in addition to solving NER without the need for supervised learning, has the following advantages

- the model output is interpretable

- it is more robust than supervised models to adversarial input examples

- it helps address an underlying challenge facing NER models (described in the next section).

The limitations of this approach are also examined below.

The solution described here while similar in spirit to the NER solution published back in Feb 2020, differs in crucial details of the solution which enables it to perform fine-grained NER at scale - it is used to label 69 entities that fall into 17 broader entity groups, across two domains - biomedical space as well as patient identities/health information(PHI) space. Moreover, the approach offers a general solution that may be applicable to a few other language and vision tasks.

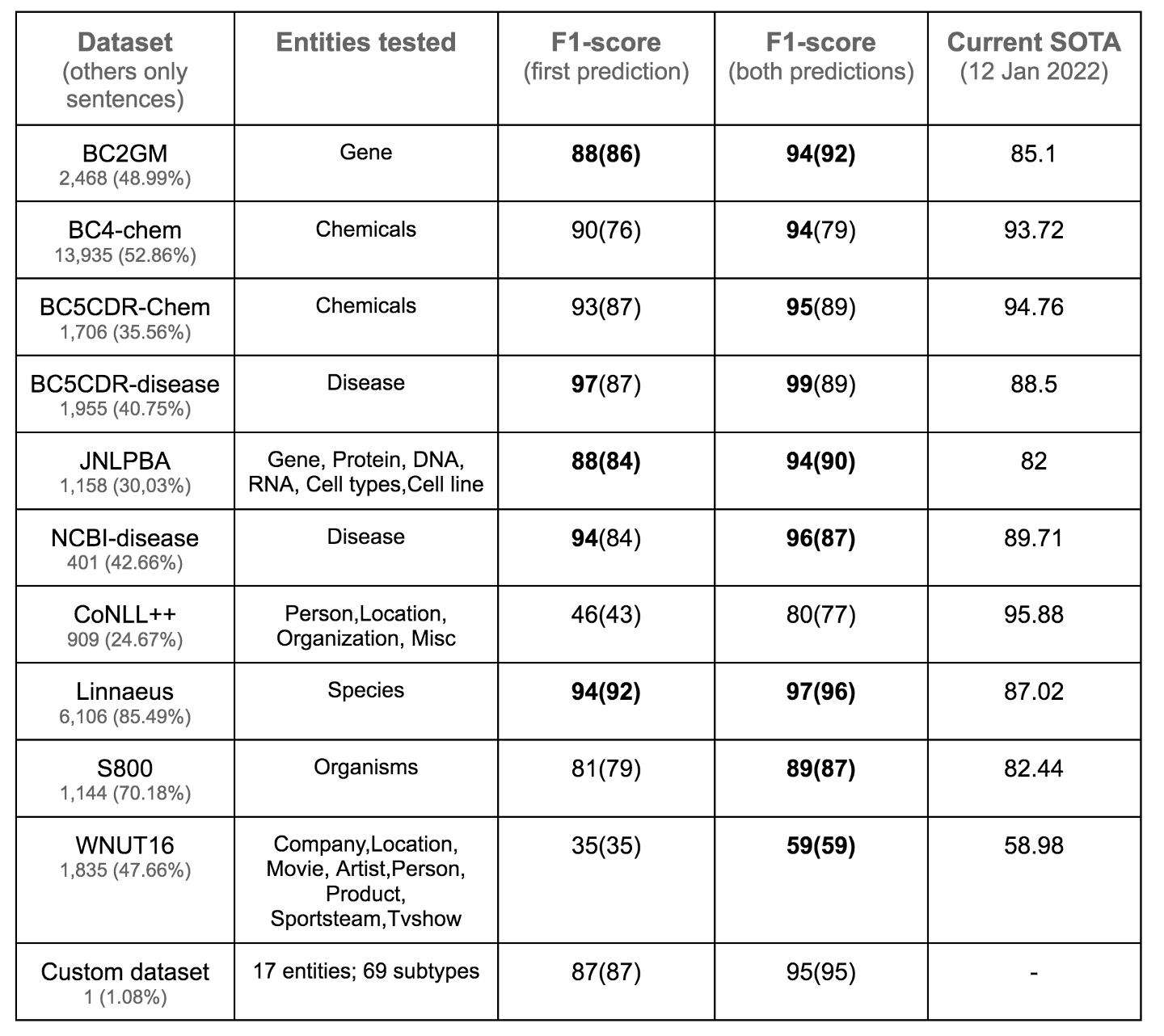

The performance was tested on 11 datasets. It performed better than the current state-of-art on 3 of them, close to state of art on 4, poorly on 3 datasets (the eleventh is a custom dataset in the process of being created to test all 69 entities). These results are examined in the model performance section below. In addition model robustness to adversarial input is also discussed below.

Code for this approach is available here on Github

Hugging Face Spaces App to try this approach

Hugging Face Spaces app to examine BERT models

An underlying challenge for any NER model

The state of art performance numbers of supervised models on NER benchmarks may suggest NER is a solved task. NER performance in real-world applications reveals a different view. Some of the challenges facing NER models in real-world applications are illustrated in Figure 1. Among all those, there is one challenge that even humans could potentially struggle with and has a direct bearing on model performance. Models struggle with this challenge, regardless of being supervised or unsupervised/self-supervised. This challenge becomes apparent to us when we have to predict the entity type in a domain we are not experienced in - e.g. legal language involving legal phrases. The challenge is described below.

Given a sentence, and a word/phrase ( the term “word” and “phrase” used interchangeably below ) such as XCorp in the sentence below, whose entity type needs to be determined,

Lou Gehrig who works for XCorp and lives in New York suffers from Parkinson’s

we have two cues for predicting the entity type:-

- Sentence structure cue - the structure of the sentence offers a cue to the entity type of the phrase. For instance, even with the word XCorp blanked out as shown below, we can guess the entity type is Organization

Lou Gehrig who works for ___ and lives in New York suffers from Parkinson’s

- Phrase structure cue - the word or phrase itself offers a cue to the entity type. For instance, the suffix Corp in the word XCorp reveals its entity type - we don’t even need a sentence context to determine the entity type.

The entity type we can infer from both these cues may be in agreement as in the case of XCorp in the sentence above. However, that need not always be the case. The sentence structure cue alone may suffice (regardless of the phrase structure cue being in agreement with sentence structure cue ) in cases where only one entity type makes sense for a blanked position as in the case of Lou Gehrig or Parkinson in the sentences below. We can swap the words in the two blank positions and their entity types are swapped too, driven by the sentence structure cue (regardless of the phrase structure cue being in agreement with sentence structure cue )

____ who works for XCorp and lives in New York suffers from ____

Lou Gehrig [PERSON] who works for XCorp and lives in New York suffers from Parkinson’s [DISEASE]

Parkinson [PERSON] who works for XCorp and lives in New York suffers from Lou Gehrig’s [DISEASE]

When we are predicting the entity type of a phrase in a sentence where multiple entity types are possible for that phrase position in a sentence, the phrase structure cue is the only cue we can go by to detect the correct entity type. For instance, in the sentence below

I met my ____ friends at the pub.

the blanked phrase could be a Person, Location, Organization or just a Measure as illustrated below.

I met my girl [PERSON] friends at the pub.

I met my New York [LOCATION] friends at the pub.

I met my XCorp [ORGANIZATION] friends at the pub.

I met my two [MEASURE] friends at the pub.

In this case, only the phrase structure cue helps us in determining the entity type - not the sentence structure. Also, in some cases, the phrase structure cue may not be in agreement with the sentence structure cue because the sentence structure cue may be skewed, due to corpus bias, towards one of the many possible entity types, which may not match the ground truth entity type. Compounding this problem even further, even if both the cues are in agreement, it may not necessarily match the ground truth entity type. For instance, in the sentence below, the ground truth entity type may be Location, but both the cues may point towards an Organization (the phrase structure cue Colt could point to an animal [horse] too depending on the underlying corpus).

I met my Colt friends at the pub.

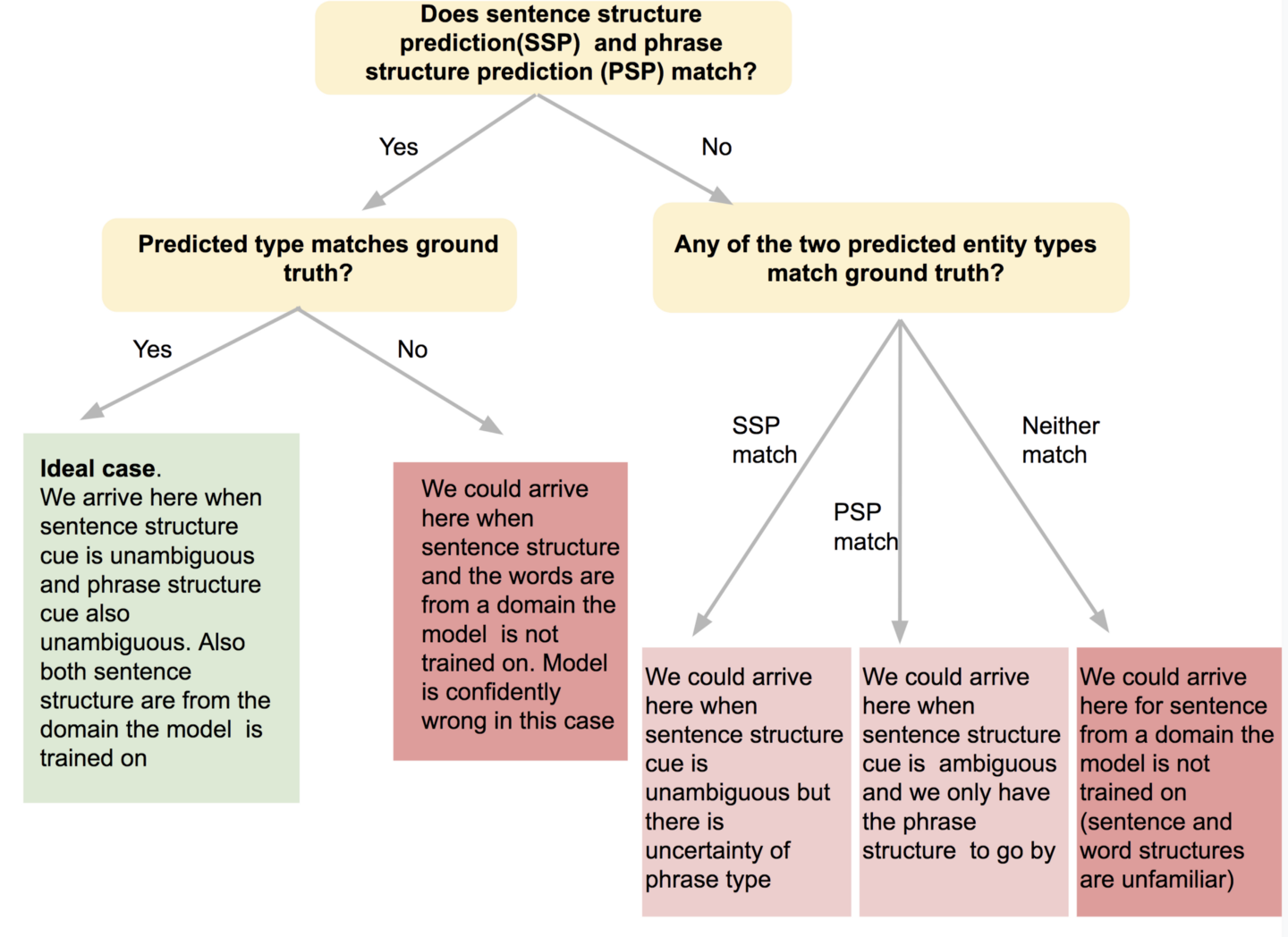

In summary, the predictions we can make, or a trained model can make for a phrase in a sentence, using the sentence structure cue and the phrase structure cue falls into one of the terminal nodes of the tree below (Figure 2).

In our case, the prediction is dependent on our expertise in the domain the sentence is drawn from. In the case of a trained model, the prediction is dependent on the corpus the model is trained on.

Figure 2. Image by Author

Supervised models tend to struggle with this challenge despite the use of manually labeled sentences - model output largely depends on the balance of representation of sentences with these different entity types in the train set, as well as the knowledge of word structure transferred from a pretrained model for the supervised learning step(fine-tuning).

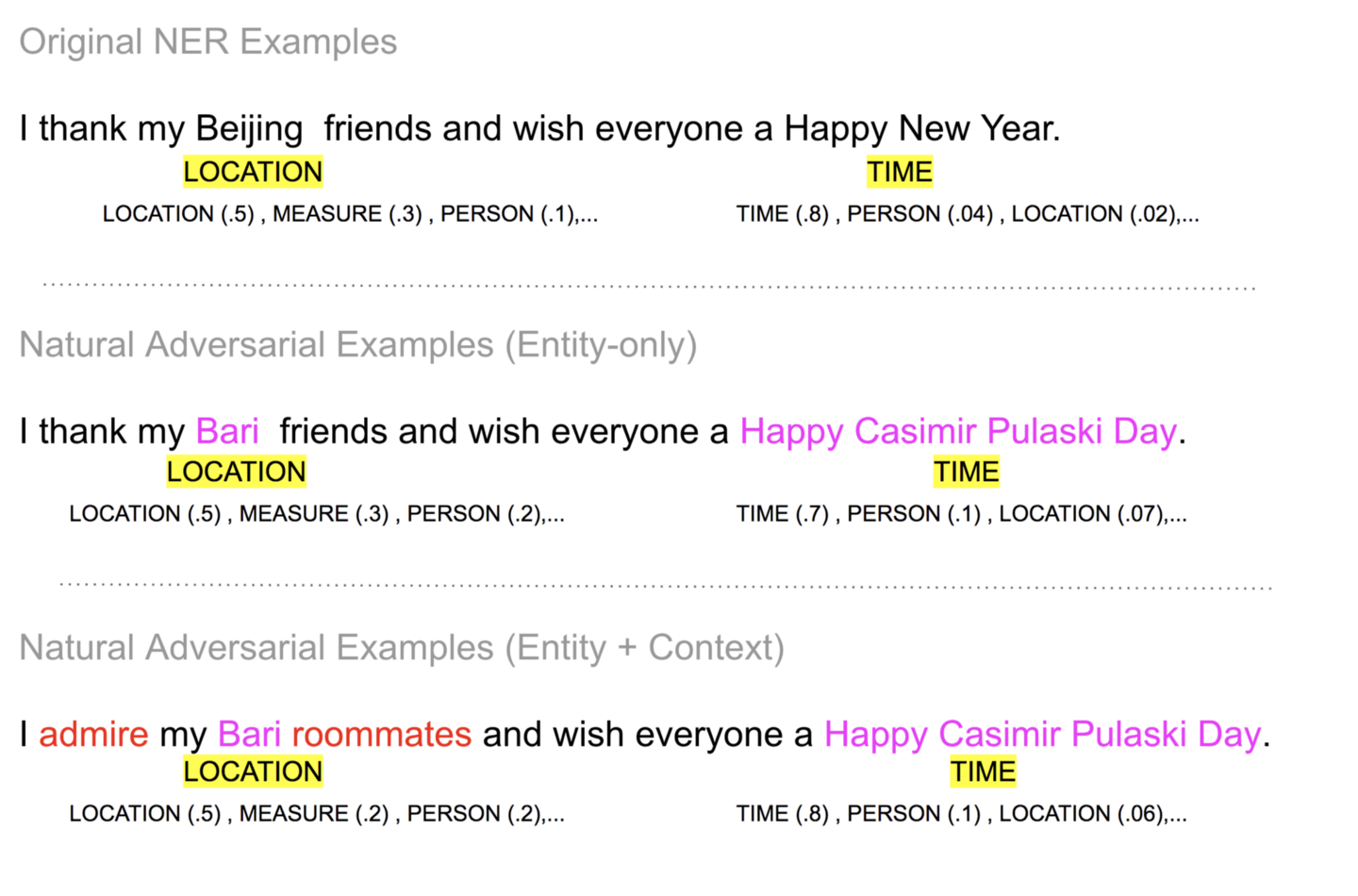

A recent paper examines the robustness of NER models by crafting two adversarial attacks -

- change in the phrase structure cue (called entity level attack in paper) and

- change in sentence structure cue (called context level attack in paper) by selective replacement of certain words in the sentence that capture context more than other words.

Barring minor differences, in spirit, these two adversarial attacks examine model performance for a couple of the cases in the challenge outlined above.

The SSL-based approach described here offers a solution to this challenge that is both robust and interpretable.

Gist of the approach

A BERT model when trained self-supervised with masked language model (MLM) and next sentence prediction objectives, yields (1) learned vocabulary vectors and (2) a model.

- The vocabulary vectors (~30k) are a fixed set of vectors that capture the semantic similarity between vocabulary words. That is, the neighborhood of each term in the vocabulary captures the different meanings of that word in the various sentence contexts it could appear in a sentence. The different meanings captured in the neighborhood of a term are determined both by the corpus the model was pretrained on, as well as the vocabulary to some degree.

- The model can transform the vectors above (when used to represent words in a sentence), to their context-specific meaning, where the context-specific meaning is captured through the neighborhood in the same vector space of the vocabulary vectors (input and output vector spaces are the same). As mentioned earlier, the prediction of the output vectors happens in the same vector space used to represent input simply because the model learns by predicting masked/corrupted vectors used to represent the input.

These two characteristics of a pretrained BERT model are leveraged to do NER without supervised learning as described below.

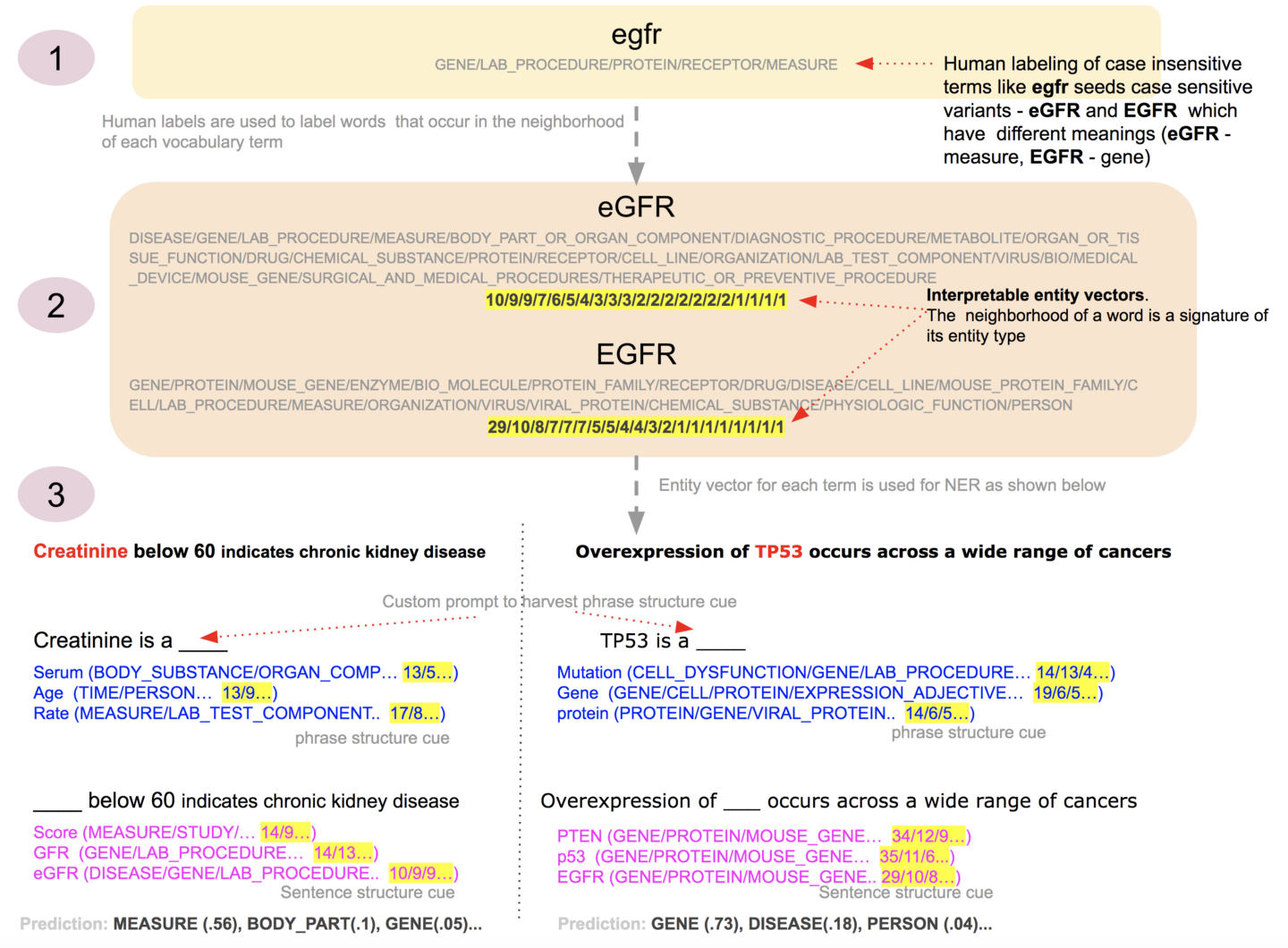

Figure 3. Gist of this approach - described in the bullet points below. The entity vectors are representative samples. The true counts of eGFR and EGFR are ~20 times more than shown in the figure. Image by Author

-

A subset of terms in a BERT model’s vocabulary is manually labeled with the entity types of interest to us. This manual labeling serves as a bootstrap seed to harvest interpretable vectors. An example of this is step 1 in Figure 3 above - labeling of a term like egfr disregarding case.

-

The manual labeling could, to some degree, be both noisy and incomplete because it is not directly used to label entities in an input sentence. Instead, the manually labeled terms are used to algorithmically create an interpretable entity vector for each word in a model’s learned vocabulary. An entity vector is simply the aggregation of all the labels of those manually labeled vocabulary terms that show up in the vector neighborhood of a vocabulary term. We can harvest information-rich entity vectors for vocabulary terms 3 times more than the number of vocabulary terms that were manually seeded with labels. Also even for those terms that were manually seeded, the algorithmically harvested entity vectors have more entity information than the manual seed. The vector neighborhood facilitates this. The two steps described so far, are offline steps. The harvested entity vectors are used in the next step. An example of this is step 2 in Figure 3 above - algorithmic labeling of terms like eGFR and EGFR using the same manual seed egfr. Note the different meaning of these terms are separated by algorithmic labeling - eGFR almost entirely loses the Gene entity type (even if Measure doesn’t dominate in eGFR, as it ideally should, it still contributes to the entity type Measure in the sentence context for the Creatinine example), whereas EGFR predominantly becomes a Gene.

-

NER is then performed by taking an input sentence, masking phrases whose entity needs to be determined and summing the entity vectors of the top predictions for that masked position. This aggregation of entity vectors captures the entity type of a term in a specific sentence context. It is essentially the sentence structure cue. Additionally, the aggregated entity vector of each of the masked phrases is also harvested using a custom prompt sentence including each phrase. While harvesting the aggregate entity vector of a phrase, the [CLS] vector of this custom prompt is also used if usable, as explained in detail below. The entity vector of the custom prompt sentence approximates all the different entity types of a term independent of a specific sentence context. This is essentially the phrase structure cue. Both these entity vectors are then consolidated to predict the entity type of a phrase in a sentence. The prediction is a probability distribution over the entities present in the consolidated entity vector by normalizing it. An example of this is step 3 in Figure 3 above - two sentences are shown that leverage the different meanings of egfr captured by the algorithmic labeling to output the corresponding entity predictions - measure - Measure and Gene.

In the tested biomedical/PHI entity detection use case, two pretrained BERT models were used. One was a cased model pretrained from scratch on Pubmed, Clinical trials, and Bookcorpus subset, with a custom vocabulary rich with biomedical entity types like Drugs, Diseases and Genes. The other was Google’s original BERT-base-cased model whose vocabulary is rich in Person, Location, and Organization. The models were used in an ensemble mode as described below.

Implementation details

Step 1. Choice of pretrained model(s)

The choice of pretrained model or models is driven by

- the availability of model(s) that are trained in the domain of interest to us and/or

- our ability to pretrain a model from scratch on the domain of interest to us.

For instance, if we only need to tag entity types such as Person, Location, Organization, we can just do with BERT base/large cased models (cased models are key for certain use cases where the same term can have different meanings based on the casing - e.g. eGFR is a measure, EGFR is a gene.). However, if we need to tag biomedical entities like Drug, Disease, Gene, Species, etc., a model that is trained on a bio corpus would be the right choice. For use cases where we need to tag both Person, Location, Organization as well as biomedical entity types, then an ensemble of Bert base/large cased with a model trained on the biomedical corpus (with custom vocabularies predominantly made up of Drug/Disease/Gene/Species terms) may be a better choice.

For other domains such as tagging for legal entities etc., pretraining a model on such a domain-specific corpus with a vocabulary rich with domain-specific terms would be the right approach, although it may be worth checking if a pretrained model exists in public model repositories, given the cost involved in pretraining from scratch.

In general, if we have a model that is pretrained on a domain-specific corpus of interest to us with a vocabulary that is representative of all the entity types of relevance to us, then that is the ideal case - we can just use a single model without the need to ensemble multiple models. The other alternative is to choose two or more models, each strong in a subset of entities of interest to us, and ensemble them.

Step 2. Label subset of each model’s vocabulary

The performance of this approach relies on how well the entity vector of synthetic labels captures all the different contexts of a vocabulary term. While the bulk of the weight lifting for entity vector creation is done by the algorithmic assignment of labels to terms, the quality/richness of algorithmic assignment depends on the breadth of coverage of manually labeled seed.

Labels can be broadly broken into three categories, of which only a subset of the first category is manually labeled by humans (approximately 4,000 terms). Labeling of the other two is automated.

- Manual labeling of proper nouns. While this can be relatively easy, we need to make sure we label a word with all possible entity types that it may potentially have that are of interest to us. For instance, in Figure 3, egfr was labeled as both a Gene and a Measure. While we could miss some entity types for a term during the seed labeling and let the algorithmic labeling or the sentence structure cue capture the missed entity type in a sentence, to the extent possible, it may make sense, during seed labeling, for the subset of the vocabulary chosen for manual labeling, to be as exhaustive as possible in labeling all the entity types of a term.

- Labeling of adjectives and adverbs. Labeling of adjectives and adverbs that precede a noun phrase is required for harvesting the phrase structure cue for a word. For instance, to harvest the phrase structure cue for Parkinson’s in the sentence “Lou Gehrig who works for XCorp and lives in New York suffers from Parkinson’s”, we use the model predictions for the blank position in the sentence “Parkinson’s is a ______“ . The predictions for the blank position would include adjectives from the vocabulary such as “neurodegenerative”, “progressive”, “neurological” etc . Manual labeling of these adjectives can be extremely hard if not nearly impossible largely because, to determine the entity type, in most cases we need a lookahead of 2 words. That is, we not only need the first prediction but also the second prediction that follows the first prediction in a sentence that includes the first prediction (e.g. We need the predictions for Parkinson’s is a neurodegenerative __________ and Parkinson’s is a progressive _______ etc. , to clearly determine what noun the model considers these adjectives/adverbs to qualify. One may not always need the two-term lookahead for these predictions - one lookahead may suffice, but if the term “known” was a prediction, then we require the next prediction too, to determine if the model thinks it is a “known drug”, “known disease”, etc.). The labeling approach described below offers a solution to this problem.

- Labeling subwords. Manually labeling entity types of prefix subwords and infix/suffix subwords is nearly impossible too in most cases, so we just leave it to the automated method described below to label them. Examples of prefix subwords are ‘cur’, ‘soci’, ‘lik’, etc and infix/suffix are ##ighb, ##iod, ##Ds etc. Even a term like ‘Car’ is nearly impossible to manually label comprehensively at scale- it could be a full word standing for an automobile or a prefix of a person’s name “Carmichael”, a chemical substance “Carbonate”, a cell type “CAR-T cell”, disease name “Carpal tunnel syndrome”, a gene/protein name “chemotaxis signal transducer protein” etc. Also, the entity type of such a prefix word also depends on the corpus the model is trained on. Infix/suffix words are just as hard if not harder.

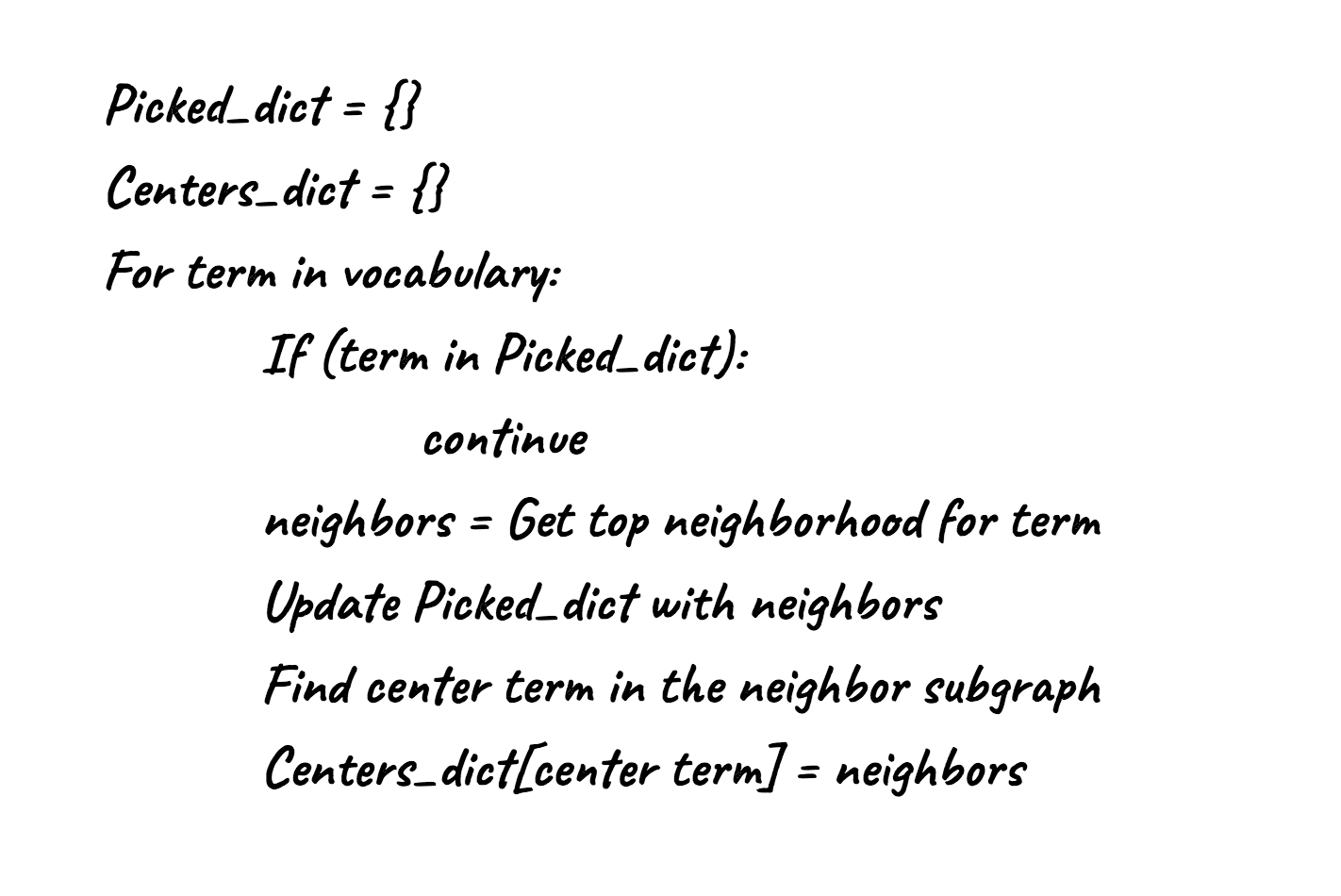

The process to label all three categories of words above is as follows. It is composed mostly of algorithmic (automated steps) with humans in the loop to seed, choose, and verify the process.

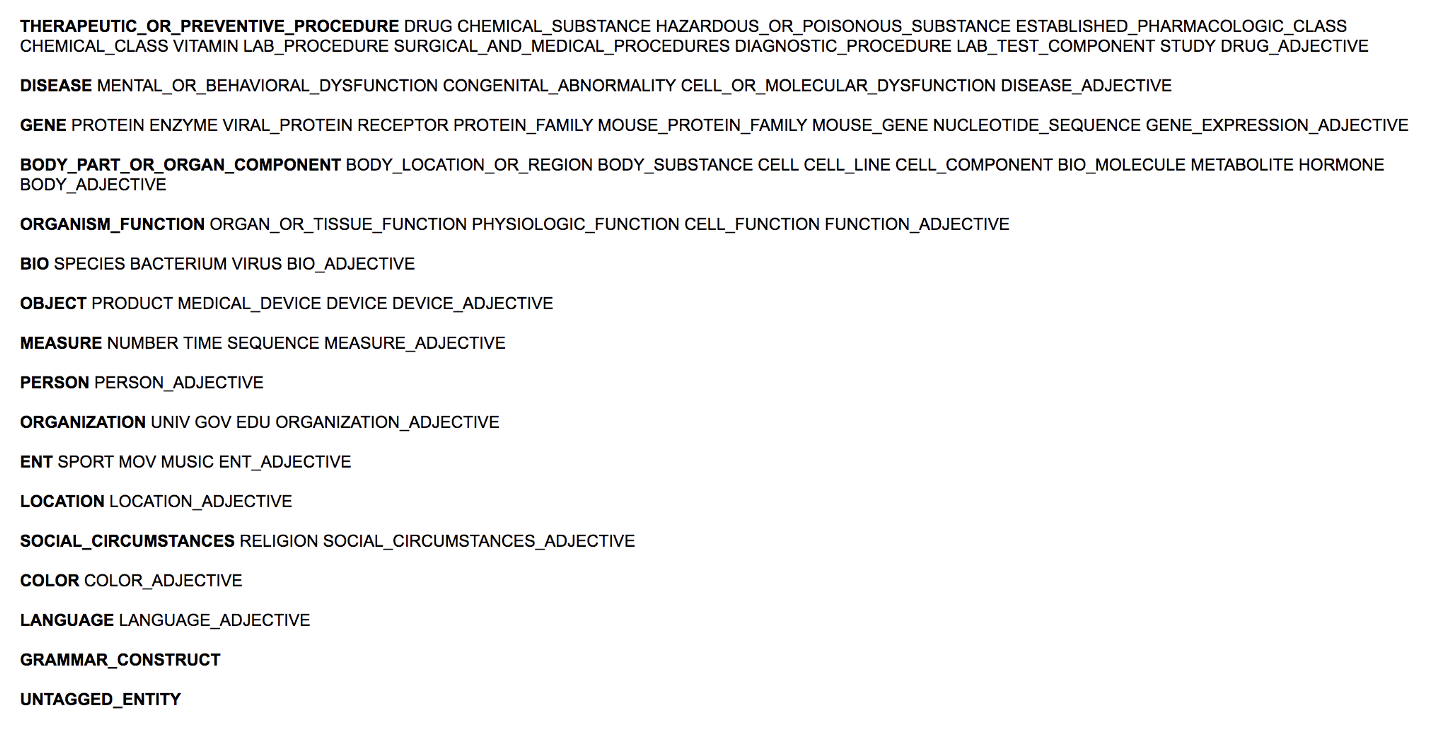

- We first decide on the different entity types we want to predict. We can have subtypes for each entity type as well. For instance, GENE could be an entity type with subtypes like RECEPTORS, ENZYMES etc. An essential subtype for any entity type X is a subtype called X_ADJECTIVE, which is used to label adjectives/adverbs. A key constraint here is to partition the entity types (along with their subtypes) into disjoint sets to the extent possible - the choice of entity label types needs to satisfy this constraint.

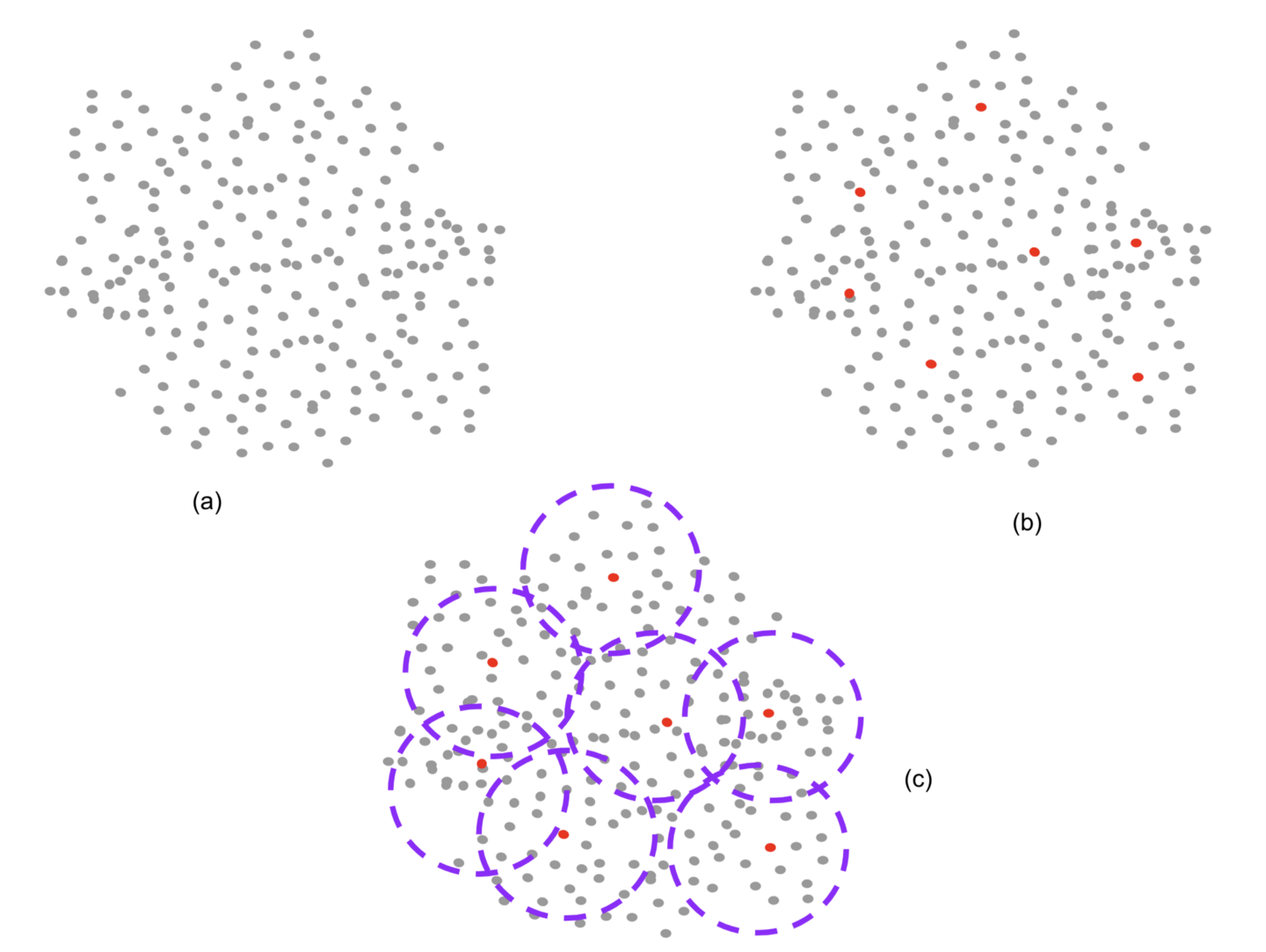

- We then start by creating clusters by examining the neighborhood of vocabulary vectors, where the center of each cluster is determined. A key characteristic of this clustering process is, these clusters are overlapping. The clustering yields roughly 4,000 overlapping clusters, for a vocabulary of size ~30,000. This is an automated step. The cluster centers are used for the next step.

- We only label all the proper nouns in this set of cluster centers. This is the seed labeling step performed by humans. It is the only step that involves humans manually labeling terms.

- We then create entity vectors for all terms in the vocabulary using these seed labels. This is done by algorithmic labeling all the terms that appear in the neighborhood of a term and aggregating those labels. The entity vector for each word is essentially the aggregation of all the neighborhoods it appears in. This is an automated step. The output of this step is the first iteration of entity vectors for all vocabulary terms. Even the entity vectors for proper nouns that were seed labeled by humans already are enhanced by this step with more entity types than what humans manually labeled for those terms. The entity vectors of adjectives are enriched further in the next step. Subword entity vectors get enriched indirectly by the enrichment of both proper nouns and adjectives.

- We construct custom prompts using just the proper nouns (the ones that were manually labeled), pass them through the model and harvest all the predictions for the custom prompt, then construct new custom prompts appending each of the predictions of the first lookahead. From this, we choose predominantly used adjectives and label them as the adjective entity type of the corresponding noun (the word adjective here is used to cover both adjectives and adverbs). This is a semi-automated step. The output of this step is entity labels for adjectives/adverbs of proper nouns/verbs.

- We repeat the entity vector creation step again to yield entity vectors for all terms in the vocabulary. This yields labels for all the three label categories mentioned earlier - proper nouns/verbs, adjectives/adverbs, as subwords. This is an automated step.

Figure 4. Schematic of the manual labeling process aided by clustering. We start by clustering the vocabulary vectors along the line shown in Figure 4 below. The centers of these clusters, (approximately 4,000) are manually labeled. Given the overlap between clusters, a term falls into multiple clusters. It inherits the labeling from the nearby labeled center terms thereby both scaling the number of labeled terms by a factor of 3, as well as increasing the number of labels even for a labeled term beyond what was manually labeled. Image by Author

Figure 4a. The initial clustering with center picking is used to pick terms that are then manually labeled. Image by Author

We might have to iterate on the entire or parts of sequences of steps above to continue to improve the entity vectors, particularly those of subtypes (to get the ordering of subtypes correct within a type). Also if we plan to have multiple models to be used in an ensemble, we will have to iterate on the entity types each model is strong at to create the entity vectors for the adjective terms. This iteration is done at an individual model level. These labeling iterations on vocabulary, however, are more targeted iterations compared to labeling sentences for a supervised model to boost performance. Also, the effect of additional vocabulary word labeling on model performance is arguably higher, since the addition is magnified by the influence of that label in all the neighborhoods it belongs to, even if not a cluster center. One approach to consider to expand the labeled vocabulary set is to extract labeled entities from training, dev data sets. Even if only a subset may be present in the vocabulary that would still help. Also this is perhaps one way to leverage off training data sets - even though sentences are useful, the labeled terms could help.

Figure 3 illustrated the entity vector creation of a word like egfr that was manually seeded by humans. An example of automated entity vector creation of a word like ‘Car’ that could be a prefix word too, as explained above, is shown below in the biomedical corpus trained model

PRODUCT/DISEASE/PROTEIN/DEVICE/GENE/RECEPTOR/CELL_COMPONENT/CELL_LINE/DRUG/ENZYME/MOUSE_GENE/PROTEIN_FAMILY/CELL_OR_MOLECULAR_DYSFUNCTION/UNTAGGED_ENTITY

7/7/7/6/6/6/5/5/5/5/5/5/2/1

- word Car - Entity vector in Biomedical corpus trained model

An example of automated creation of entity vector for same word Car using bert-base-cased

PRODUCT/GENE/PERSON/DRUG/DISEASE/UNTAGGED_ENTITY/LOCATION/PROTEIN/CELL_LINE/MOUSE_GENE/ENZYME/DEVICE/PROTEIN_FAMILY/METABOLITE/RECEPTOR/CELL_COMPONENT/ORGANIZATION/CHEMICAL_SUBSTANCE/SPECIES/BIO/HAZARDOUS_OR_POISONOUS_SUBSTANCE/LA B_PROCEDURE/THERAPEUTIC_OR_PREVENTIVE_PROCEDURE/CELL/MEASURE/OBJECT/TIME/MEDICAL_DEVICE/DRUG_ADJECTIVE/ORGAN_OR_TISSUE_FUNCTION/DIAGNOSTIC_PROCEDURE/ESTABLISHED_PHARMACOLOGIC_CLASS/LAB_TEST_COMPONENT/ORGANISM_FUNCTION/CELL_OR_MOLE CULAR_DYSFUNCTION/VIRUS/NUMBER/HORMONE/CONGENITAL_ABNORMALITY/VIRAL_PROTEIN/SURGICAL_AND_MEDICAL_PROCEDURES/BODY_LOCATION_OR_REGION/NUCLEOTIDE_SEQUENCE/BODY_PART_OR_ORGAN_COMPONENT/EDU/CELL_FUNCTION/SPORT/ENT/MOUSE_PROTEIN_FAMILY/ SOCIAL_CIRCUMSTANCES/RELIGION/MENTAL_OR_BEHAVIORAL_DYSFUNCTION/PHYSIOLOGIC_FUNCTION/BODY_SUBSTANCE/STUDY/BACTERIUM

128/83/81/68/64/62/61/53/46/42/40/36/36/36/34/27/25/22/20/20/19/16/10/10/8/7/7/7/5/5/5/5/4/4/4/3/3/3/3/3/3/3/2/2/2/2/2/2/2/2/1/1/1/1/1/1

- word Car - Entity vector created from Bert-base-cased

An example of entity vector creation for a suffix term #imatinib . The predominant entity type is a drug as one would expect.

DRUG/GENE/DISEASE/UNTAGGED_ENTITY/THERAPEUTIC_OR_PREVENTIVE_PROCEDURE/METABOLITE/HAZARDOUS_OR_POISONOUS_SUBSTANCE/SURGICAL_AND_MEDICAL_PROCEDURES/ENZYME/PROTEIN/ESTABLISHED_PHARMACOLOGIC_CLASS/LAB_PROCEDURE/VIRUS/CHEMICAL_SUBSTANC E/PROTEIN_FAMILY/CELL/MOUSE_GENE/DRUG_ADJECTIVE/MEASURE/CHEMICAL_CLASS/HORMONE/DISEASE_ADJECTIVE/CELL_LINE/ORGANIZATION/PHYSIOLOGIC_FUNCTION/RECEPTOR/PERSON/VIRAL_PROTEIN/BIO_MOLECULE/BIO/DIAGNOSTIC_PROCEDURE/BODY_PART_OR_ORGAN_CO MPONENT/LOCATION/VITAMIN/BACTERIUM/MOUSE_PROTEIN_FAMILY/CELL_FUNCTION/MENTAL_OR_BEHAVIORAL_DYSFUNCTION/GENE_EXPRESSION_ADJECTIVE/CELL_COMPONENT/CELL_OR_MOLECULAR_DYSFUNCTION/SPECIES/BODY_LOCATION_OR_REGION/ORGAN_OR_TISSUE_FUNCTION /CONGENITAL_ABNORMALITY/MEDICAL_DEVICE/LAB_TEST_COMPONENT/SOCIAL_CIRCUMSTANCES/STUDY/POLITICS/BODY_SUBSTANCE/PRODUCT_ADJECTIVE/SPORT/ORGANISM_FUNCTION/LEGAL/EDU/PRODUCT

1138/197/174/152/112/104/68/67/58/58/48/39/35/34/31/31/30/29/28/25/24/21/20/17/17/17/16/16/15/14/13/13/11/10/9/9/9/9/8/8/7/7/7/7/6/5/4/3/3/2/2/1/1/1/1/1/1

- suffix ##atinib - Entity vector in Biomedical Corpus trained model

Few characteristics of the entity vector may be apparent from the examples above.

- the entity vector for a word is essentially the factor form of a probability distribution over entity types, with a distinct tail.

- There is some level of noise in a single entity vector. However, since both the phrase structure cue and sentence structure cue are aggregations of these entity vectors, the effect of noise tends to be muted to a large degree (explained further in the next section).

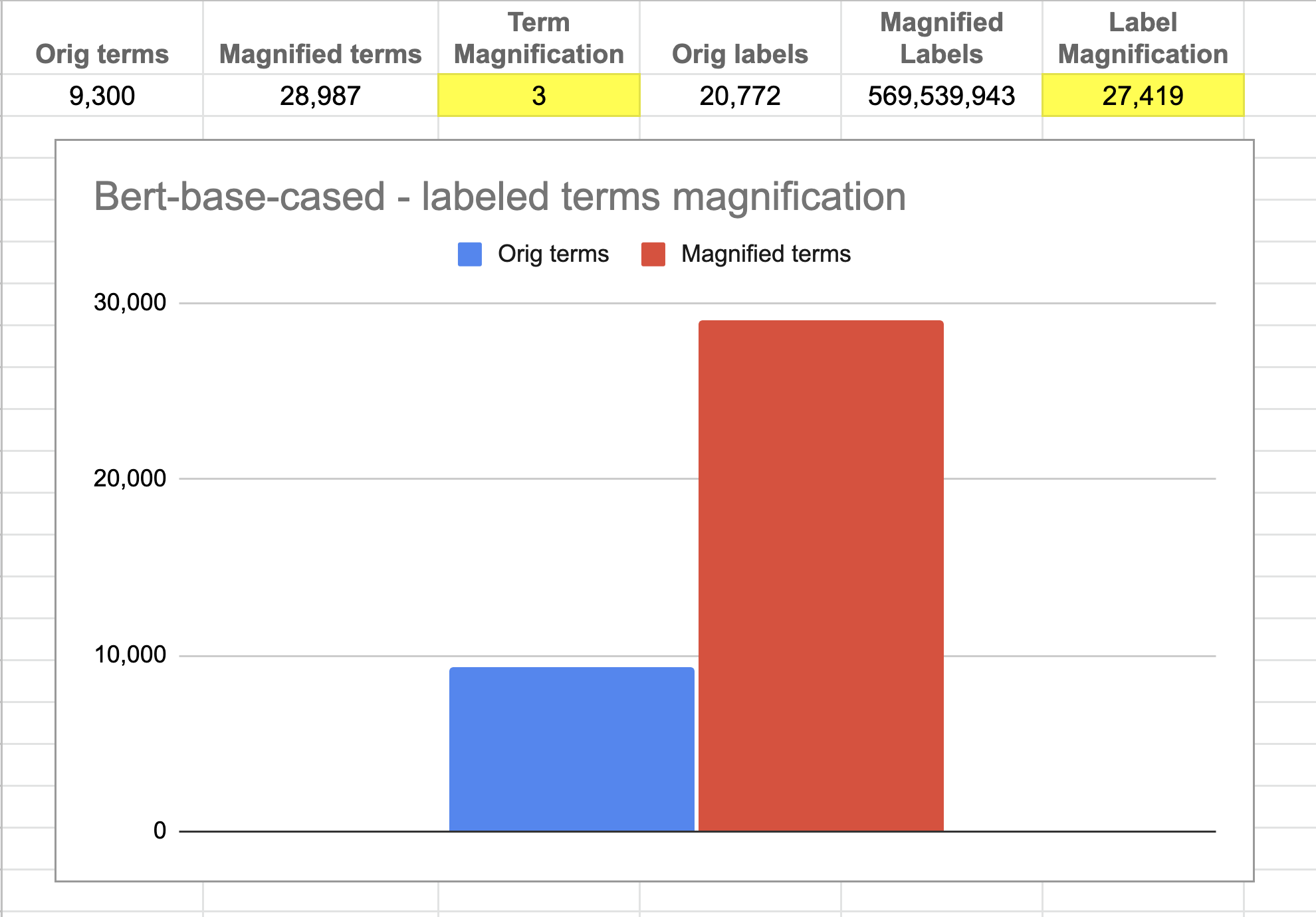

Figure 4b1. Label magnification of bert-base-cased model. About 9.3k human-labeled terms are magnified 3 times to create ~29k terms. The original label strength of 20k is magnified 27k times to 569 million labels. The performance of this approach relies on this magnification. Image by Author

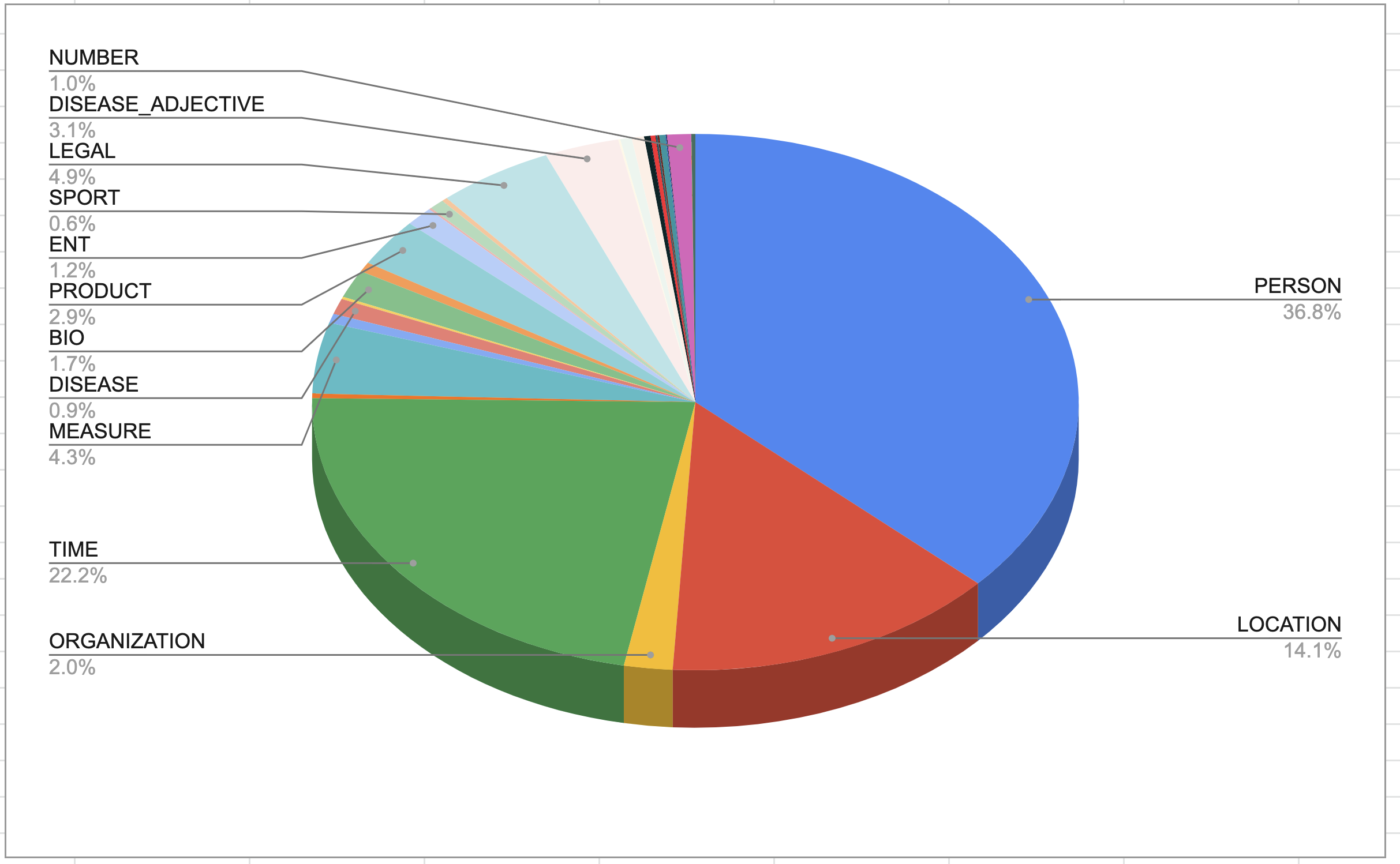

Figure 4b2. Figure 4b2. Entity distribution in bert-base-cased model obtained with label magnification. Image by Author

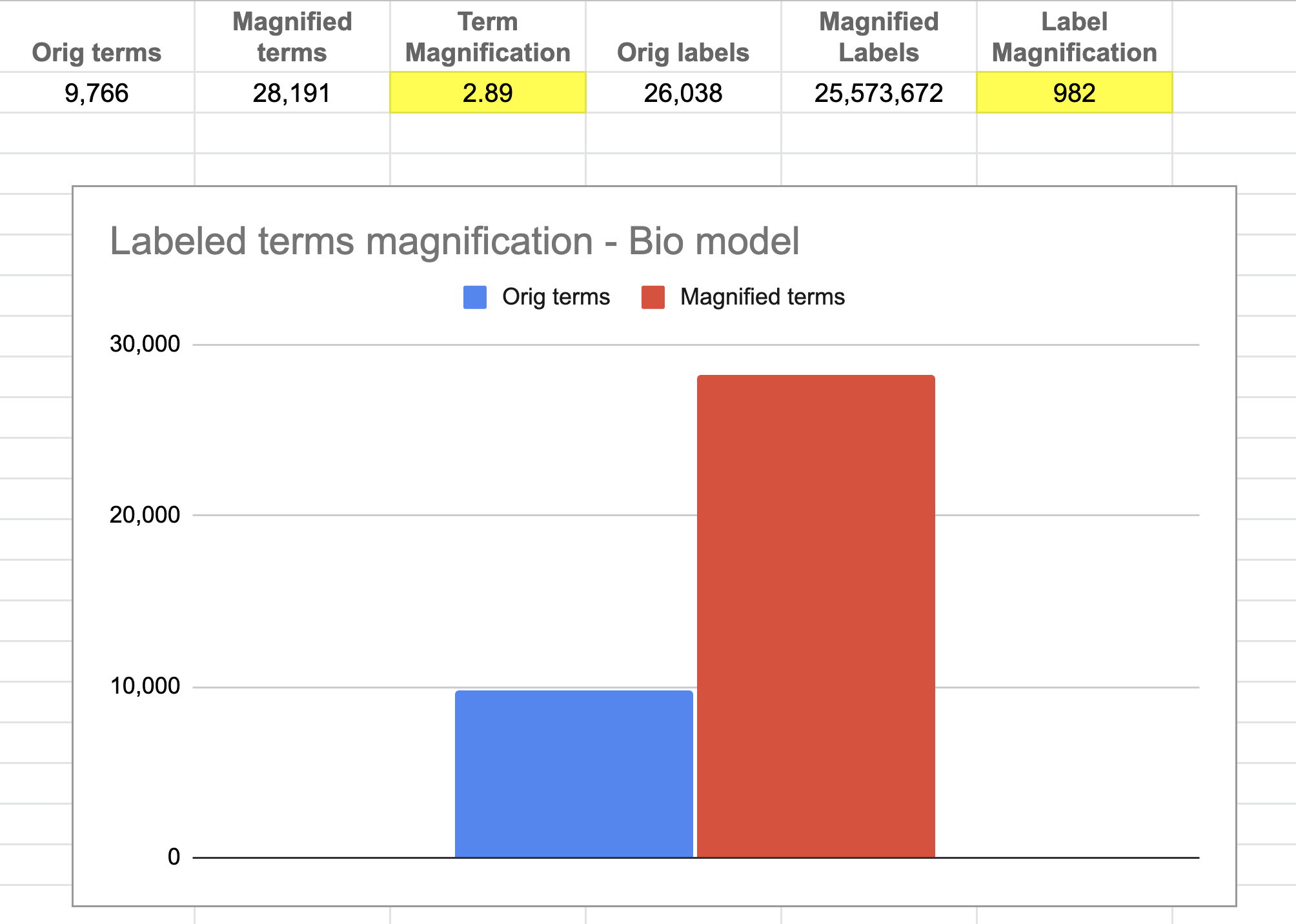

Figure 4b3. Figure 4b3. Label magnification of Bio model. About 9.7k human-labeled terms are magnified 3 times to create ~29k terms. The original label strength of 26k is magnified 982 times to ~26 million labels. The performance of this approach relies on this magnification. Image by Author

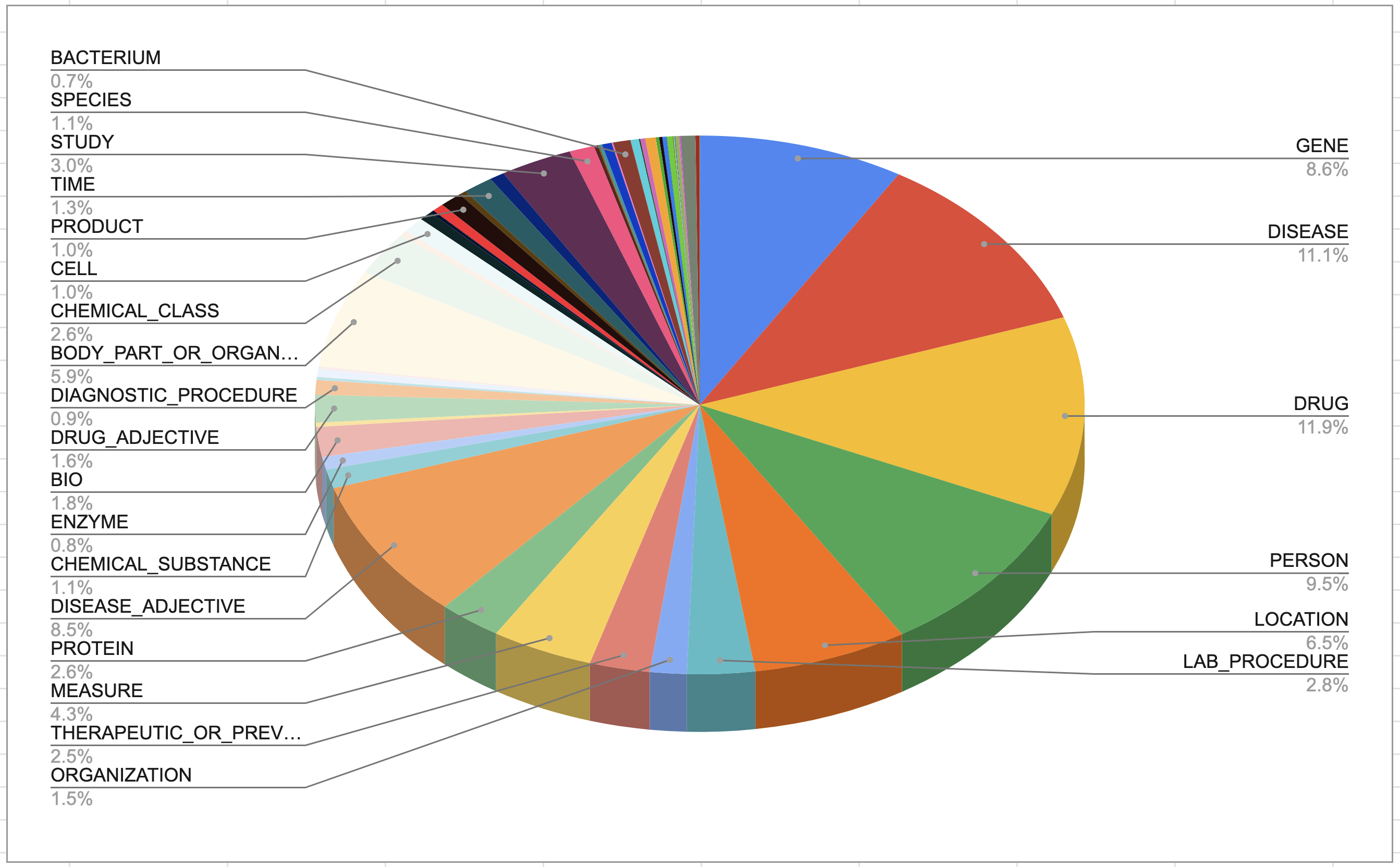

Figure 4b4. Figure 4b4. Entity distribution in bio model obtained with label magnification. Image by Author

Step 3a. NER prediction at an individual model level

Given an input sentence, for each word/phrase in the sentence whose entity type needs to be determined, harvest model predictions (vocabulary vector words) for that word. The model predictions for computing both sentence structure cue and phrase structure cue are harvested with one invocation of the model. For instance, if we want to predict the entity type of Lou Gehrig and Parkinson’s in the sentence

Lou Gehrig who works for XCorp and lives in New York suffers from Parkinson’s

we construct 4 sentences, two for each word - one to harvest predictions to construct phrase structure cue and the other for sentence structure cue.

- [MASK] who works for XCorp and lives in New York suffers from Parkinson’s

- Lou Gehrig is a [MASK]

- Lou Gehrig who works for XCorp and lives in New York suffers from [MASK]

- Parkinson’s is a [MASK]

In general, to detect entity types for n words in a sentence, we construct *2n** sentences. We construct a single batch composed of the 2*n sentences (taking care to include padding to make all sentences the same length in a batch) and invoke the model. In some use cases, we may want to only find entity type for a specific phrase, while in others we may want automatic detection of phrases. If it is the latter use case, we use a POS tagger to identify phrases.

Few details that help improve performance

- Cased models tend to perform better than uncased models for the biomedical domain since they can leverage the casing cue that separates words that have different meanings based on the casing - e.g. eGFR and EGFR if present in the text.

- When using cased models for prediction, modifying the casing of input selectively, tends to improve model predictions. For instance, if Mesothelioma is a word in the vocabulary and not mesothelioma, then modifying the casing of mesothelioma in an input sentence to match the casing in the vocabulary avoids breaking a word into subwords. This improves the descriptor predictions (particularly when a word would otherwise be broken into multiple subwords).

- When we harvest model predictions (descriptors) for the phrase structure cue using the custom prompt sentence, say “Parkinson’s is a [MASK]” , if the model’s [CLS] vector has been trained with next sentence prediction and has quality predictions when tested against a random sample of phrases, then we can utilize descriptors for the [CLS] vector prediction along with the prediction for the masked position. For instance, the top predictions for the [CLS] position for the sentence from the model trained on biomedical corpus are “Parkinson’s is a [MASK]” are Progressive, Disease, Dementia, Common, Infection etc. These descriptors are used along with the top predictions for the [MASK] position - neurodegenerative, chronic, common, progressive, clinically, etc.

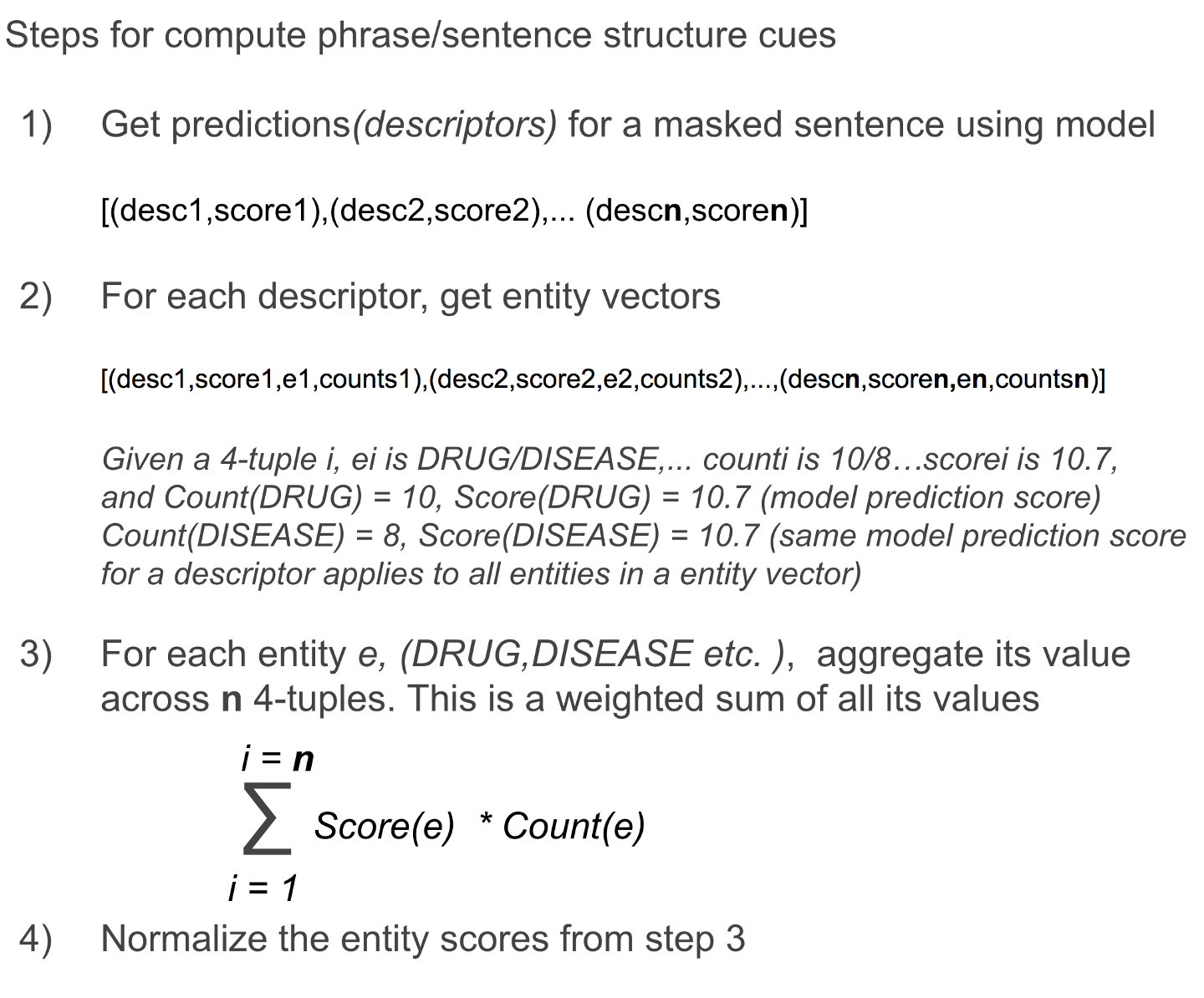

The computation of the phrase structure cue and sentence structure cue is identical and shown in Figure 5 below. The entity vector for each descriptor goes through a softmax prior to the weighted sum below (not shown in the figure below). This serves to reduce the effect of labeling count imbalances - particularly the absolute counts in the signature of a descriptor from dominating, despite accentuating the winner take all (natural effect of softmax) characteristic already present at an individual descriptor level (entity signatures have a distinct tail).

Figure 5. Steps to compute phrase and sentence structure cues. Image by Author

Each model used in an ensemble outputs a phrase structure cue and sentence structure cue for each word that is being predicted.

Step 3b. Ensemble model predictions

Ensemble results from the models, prioritizing the predictions based on the strength of the model for a specific entity type within a sentence. The ensemble essentially chooses the output of these models based on the entities they are exclusively or non-exclusively good at predicting. When choosing a model’s prediction, a factor that determines the importance of its output is, if the model is predicting entities that fall into its specific domain of strength or it is predicting entities outside the domain of its strength. This signal is of value to address the cases where a model is confidently wrong (second terminal node in Figure 2) or is not sure at all of its output (fifth terminal node in Figure 2). The ensemble output could be just one prediction when both models agree or two when they don’t agree. The percentage of dual predictions across the 11 test sets varies from 6% to 26%. The output of supervised models, in comparison, for these dual prediction cases would be largely driven by the train set balance between sentences supporting either of these predictions, with the choice of one of them being equally likely when both are equally represented.

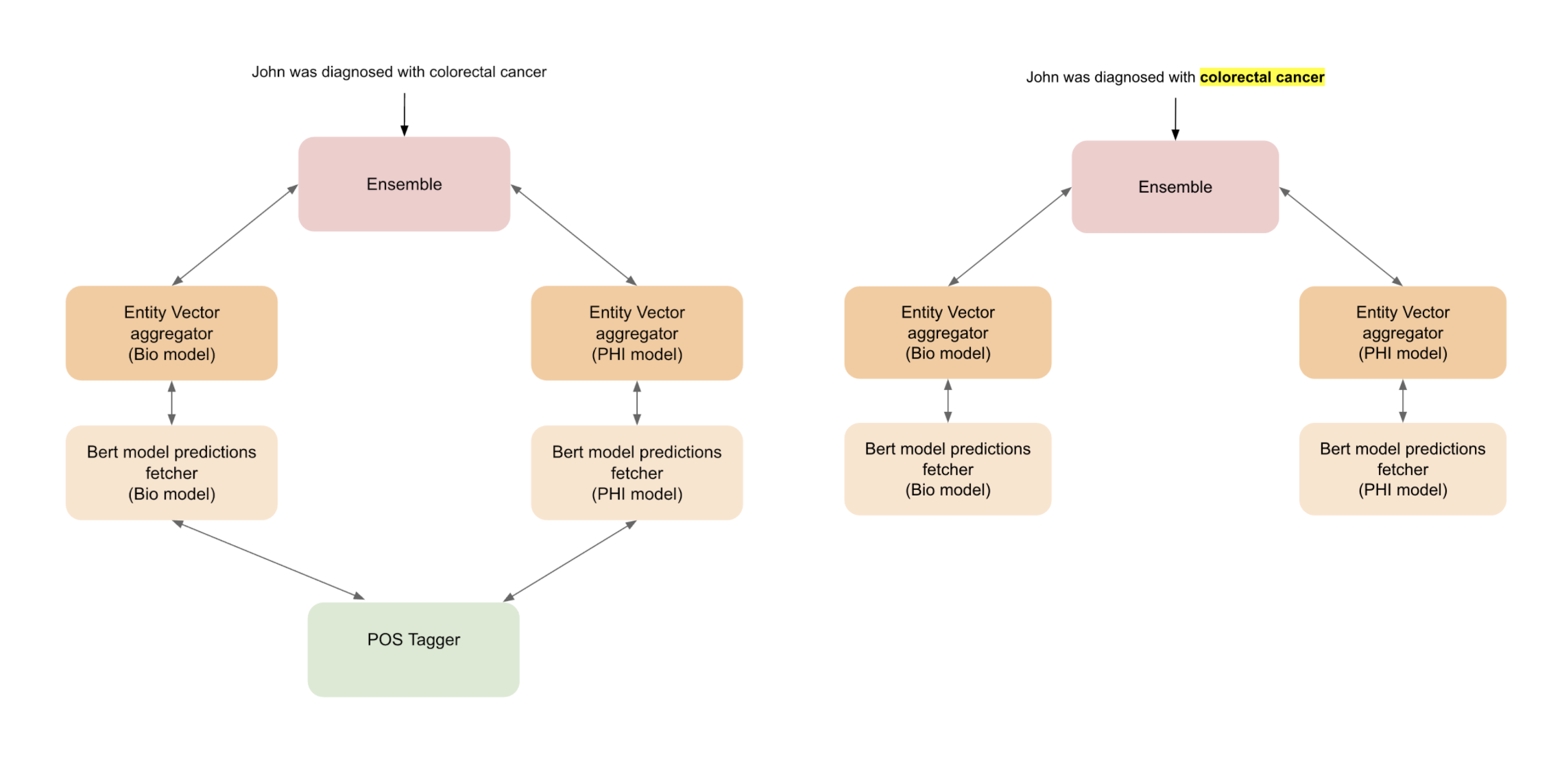

Figure 5a. The two use cases of the model. In one use case, the input phrase spans are determined by a POS tagger and the phrase spans are tagged. In the second use case, the phrases in the input sentence to be tagged are explicitly specified during input (e.g. colorectal cancer). In the second use case, the POS tagger is not used. Image by Author

Ensemble performance

Evaluating a self-supervised model on test set designed for a supervised model

Two use cases of NER in applications (figure 5a) are examined below since they have a bearing on how the ensemble model performance is evaluated on popular benchmarks designed for supervised models.

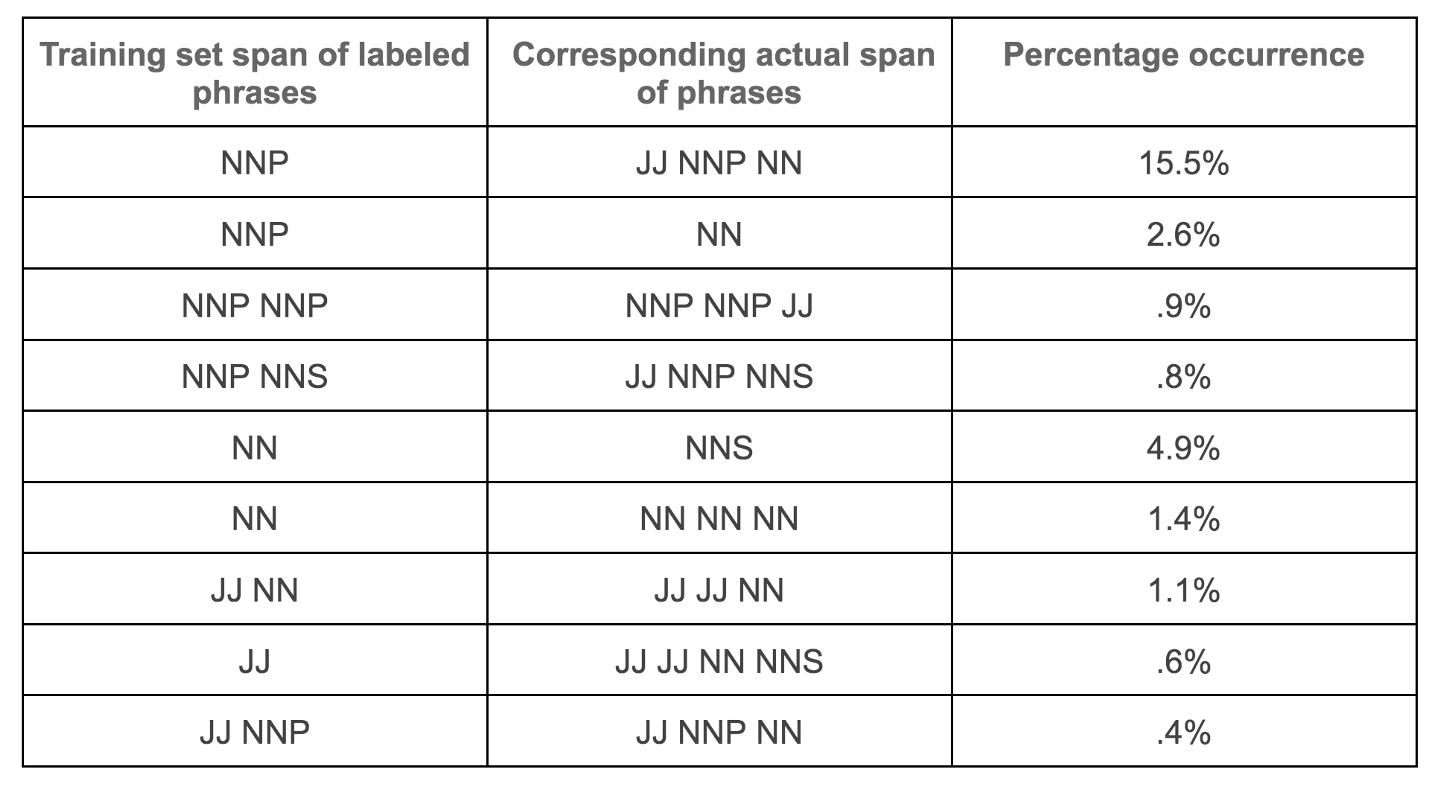

- Given any sentence, identify the entity types of all noun/verb phrase spans. This is the predominant use case that is targeted to train a supervised model. The task of identifying phrase spans is baked into the model during the supervised training process along with the ability to detect entity types. The definition of a phrase span, in this case, is implicitly captured in the labeling of phrase spans in the train/dev set. Test set then largely contains sentences with phrase spans consistent with the definition implied in the train set. The problem however of the model learning “what a phrase span is?”, implicitly from the labeled train set phrase spans, is that their labeling in the train set needs to be consistent (which is not always the case in practice as one can see from the inconsistent phrase span specifications in the train set. See Figure 5b below). Also, the train set driven implicit definition of phrase span limits a supervised model’s capability at test time to label phrases. For instance, consider the example in figure 1 ” he was diagnosed with non small cell lung cancer” . If the model training was labeling only the term cancer , then we lose critical information on the type of cancer. Also adding to the complexity is the fact that the extent of a phrase span could change the entity type. In the example of cancer in figure 1, the entity type remains the same regardless of we pick cancer or non small cell lung cancer as the phrase span. However, in the sentences, again from Figure 1, “I met my New York friends at the pub”, “I met my XCorp friends at the pub”, if we just chose the phrases in bold, NER would yield Location and Organization . However, if we consider the phrase spans “I met my New York friends at the pub”, “I met my XCorp friends at the pub” , a NER model needs to tag them both as Person . In summary, the benchmark datasets (designed to evaluate supervised models) implicitly defining phrase spans in the training data poses a challenge, when the definition is not consistent. Even more importantly, any definition of what a phrase span is, that is baked into the training set, and therefore into the supervised model, is inaccessible to a self-supervised model since it does not learn those implicitly baked rules from the train set (More examples below).

- Given a sentence, and specific phrases within a sentence, identify their entity types. The specific phrase could be proper subsets of phrase spans or complete phrase spans. An example of this use case is relation extraction - where we have a phrase with a particular entity type and we want to harvest all relations involving it and other terms of a particular entity type. For instance, consider the term ACD in figure 1, which has different entity types. Let’s say, we want to find all sentences where ACD is used to mean a Drug , and is present in the sentence along with a Disease. The goal is to determine if ACD treats the disease or if the disease is an adverse effect caused by ACD . Supervised models are generally not suited for this use case unless the phrase spans required for the task are consistent with the phrase spans the model was trained on.

The self-supervised NER approach described in this post decouples the task of identifying phrase spans from entity recognition task. This makes it possible for it to be used in both use cases described above. In the first use case, we use a POS tagger to identify phrase spans. In the second case, we identify entity types of the explicitly specified phrases in a sentence. However, evaluating this approach on standard benchmark test sets designed for supervised learning poses the challenge already mentioned above

- Since we do not have a learning step on the train set to learn the phrase spans definition implicit in the train set. If the specification of phrase spans is not consistent, which is indeed the case in the popular benchmarks, the consistent identification of phrase spans (e.g. use of adjectives preceding noun phrases as in “he suffers from colorectal cancer”, or just picking contiguous noun phrase sequence as phrase spans, he flew from frigid New York to sunny Alabama ) by a POS tagger which we can control by the chunking, may still yield phrase spans not matching the test set phrase spans. In cases, where the entity type of phrase spans changes based on what is included (XCorp friends vs XCorp friends in figure 1) the predictions would be considered wrong even if in reality the ensemble model prediction was correct.

- To circumvent this problem, the evaluation of the ensemble on the benchmark test sets was done by treating the test set as though it was the second use case. That is, a sentence and the phrase spans are given - the model has to detect entity types. This enables us to be oblivious to the variations in phrase span definition across data sets and the inconsistencies in phrase span definitions implicitly captured in the train set. However, this implies we lose the capability to find false positives (with respect to OTHER tag) since the phrase spans are already given. That is, all other terms in the sentence are trivially tagged as “OTHER”- we forfeit the capability of identifying error cases when the model would have tagged a term or phrase not in the phrase span as an entity that is not “OTHER” - false positives. Another way to look at this is that we are told what terms are “OTHER” and we are just asked to tag entities in a sentence that is not “OTHER”. For this reason, the model performance on “OTHER” is not factored in the output, since the model prediction is always correct - it would artificially boost performance. The model performance is the average of all entities to be tagged except “OTHER”.

- Interestingly we do get an opportunity to evaluate the model false positive rate (with respect to OTHER tag) in all the benchmarks, except with a twist. In the 10 benchmark datasets used to evaluate model performance, the number of sentences with just the “OTHER” tag ranged from 24% to 85% as shown in figure 7 below. These sentences were treated as use case 1 sentences (Given any sentence, identify the entity types of all noun/verb phrase spans), and the false-positive rates of tagging OTHER as other entity types (being tested in that test set) was counted. The performance numbers in Figure 6, factor the reduction in precision for an entity type due to these sentences. The twist is that these sentences with “OTHER” tags actually include sentences with entity types that could qualify as legitimate entity subtypes given the fine-grained entity types this approach detects (examples in the Additional detail section at the end of this post). So a large proportion of the false positives are not false positives but true positives if the entity type was as broad as it is defined in the current approach. To illustrate this, the model performance ignoring the false positives in the “OTHER” only sentences are listed in Figure 7 below. The performance is above state of art in 5 out of the 10 benchmarks with this relaxed evaluation not including false positives of model tagging an entity as other (note a PERSON being tagged wrongly as LOCATION is trapped and factored into the F1-score computation) - which is, needless to say, is listed purely to illustrate the point mentioned above.

Figure 5b. Sample of labeled phrase spans from one of the dataset test sets (BC2GM). In general human-labeled phrase spans tend to be inconsistent with some phrases matching the full phrase span length (e.g. contiguous NN/NNP) and in other instances, they tend to be smaller in length than actual phrase spans. Examples of these inconsistent phrase span labeling are present in the dataset subdirectory in the Github repository. Image by Author

As an aside, Perhaps supervise models may get a boost in performance if phrase spans are handled consistently both at training and test time by coupling them with a POS tagger (i.e. using the output of a POS tagger as input to the model along with the sentence of interest) - not just as an additional feature (as many supervised models already do) but as a means to give the model a hint to what part of a phrase is to be tagged in an input. For instance, if any input to the model is accompanied by a POS tagger signal that indicates which segment of a sentence is of interest (and tagging others with another symbol analogous to O), then it may offer a cue for the model which phrase is expected to be predicted. For instance, if the intent is to tag just cancer in “he was diagnosed with non small cell lung cancer”, then only the POS tag symbol could be a symbol like NNP - all others could be just O. If the intent was to that the entire phrase *non small cell lung cancer* in the same sentence, then all symbols other than that could be O, in the input.

General observations on model performance

These are the general observation of model performance across diverse tests with entity types that were sufficiently seeded by the manual labeling as well as entity types that were inadequately seeded by the manual labeling (continual labeling for select entity types is an ongoing process to improve model performance just as it is with a supervised model using labeled sentences).

- ensemble performance exceeds state-of-art in cases (3 datasets) where the labels being tested have rich entity vectors. Additionally the sentences in these test sets where the model performed well, have sufficient context. Lastly, for test sentences with the ambiguity of entity types, the phrase and sentence structure cues in combination are sufficient to match the ground truth entity type.

- ensemble performance is close to(4 datasets) or well below (3 datasets) state-of-art in cases where the labels being tested have moderate/poor quality entity vectors. Additionally the sentences have insufficient context for the model to perform well (e.g. short sentences). Lastly, for test sentences with the ambiguity of entity types, the phrase and sentence structure cues are insufficient to match the ground truth entity type without skewing the model output towards a specific entity type - these were largely sentences where both predictions could apply and the choice in the test set was the second choice in this approach (leading to model performance drop when picking only the first one - dual prediction evaluation does better for this reason) . Supervised learning addresses this by forcing the model to pick a particular label in cases of ambiguity during training, thereby skewing the model to pick a particular entity type on test sets. No additional labeling even at the word level using the train set was done with this approach. The train and dev sets are not used at all as mentioned earlier - the ensemble was directly tested on the test set. While supervised models can, having primed on a train set, do better on test sets in cases where it has been primed to pick one entity type in cases of ambiguity, it is not clear the higher performance thus gained carries to production use, for cases where the model output was primed away from, show up. Also, the learning on train set does not always help in production use, particularly for out-of-distribution words or sentences. The adversarial attack on the supervised model discussed below reveals this weakness of supervised models to some degree. Additionally, the NER approach described here is more robust in part because of the number of sentences a model is trained on, which in practice, is almost always several orders of magnitude greater than the train set. This reduces imbalances in sentence structures, even if present. Lastly, even in cases, the ensemble output does not match the expected output, the interpretable entity vectors offer insight. This helps particularly in cases where certain entity types are inadequately labeled.

Figure 6. Model performance using only the first prediction or the best of top two predictions when the model outputs dual predictions. BC2GM, BC4,BC5CDR-chem, BC5CDR-Disease, JNLPBA, NCBI-disease, CoNLL++, Linnaeus, S800, WNUT16. Image by Author

Figure 7. Model performance not factoring sentences with just “OTHER” tag. See the additional details section on model performance for more details on this. Image by Author.

The F1-scores above are computed by counting model predictions at a token level as opposed to an entity level. Also, the F1-score is the average of all entities (except OTHER) as mentioned earlier.

Performance on adversarial examples

The robust performance for the example sentences in the figure below, showcased in the recent paper examining the robustness of NER models, is a natural consequence of the use of pretrained models as is, with no further supervised learning on a labeled data set. The adversarial attack is constructed by taking the sentence “I thank my Beijing…” and first transforming it by just replacement of select entities that are chosen out-of-distribution relative to the training set for a supervised model. In the next adversarial attack, the sentence undergoes a second transformation - some words in the sentence capturing sentence context are replaced to examine how robust models are to context-level word changes.

The results below demonstrate the ensemble performance is not only robust to both the changes in that the top prediction does not change, but even the predicted distribution for a term also remains nearly the same across all three sentence variants.

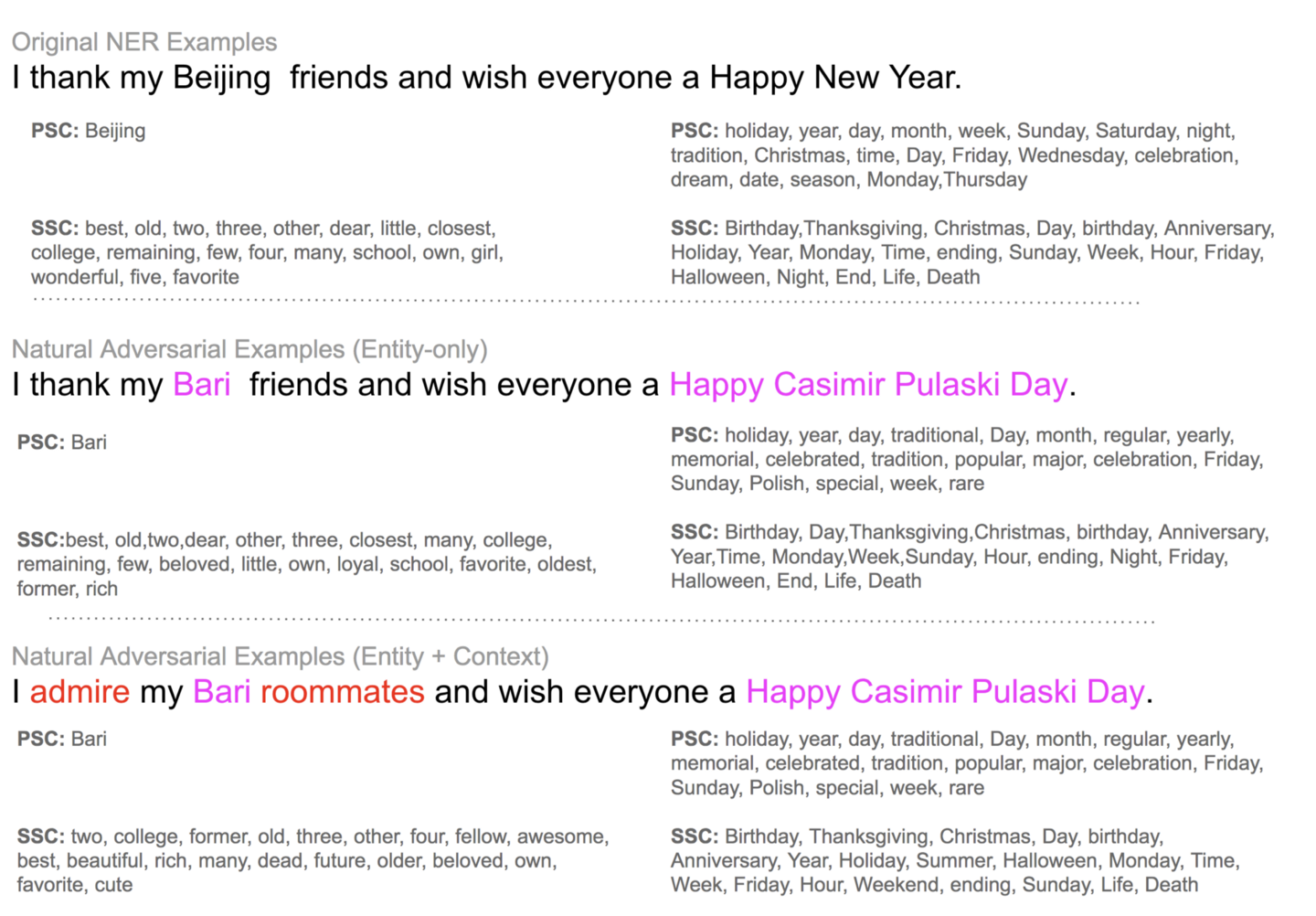

Figure 8 Model predictions for the adversarial examples remain constant. Examples from paper Image by Author

Also, unlike supervised models where the only insight we can get into what the model is doing is limited largely to the probability distribution over entity types, we can clearly trace how the probability distribution was arrived at with the approach described here. This is one of the key benefits of this approach - the output is made transparent by the use of interpretable entity vectors. For instance, in the example sentence above, the model predictions constituting the phrase structure and sentence structure cues are shown. They remain almost the same across all three sentences, clearly demonstrating the predictions are invariant across the three sentences. Also, the sentence structure cue predictions for the position “I met my ___ friends…” clearly show the ambiguity of entity types - it is a mixed grabbag of counts (two/three), adjectives for persons (best, closest, favorite, former), organizations/locations (college, school). Sentence structure cue heterogeneity is a useful indicator to leverage off to decide when we have to rely on phrase structure cues to derive the answer.

Figure 9 Model entity vectors for the adversarial examples remain constant. Examples from paper Image by Author

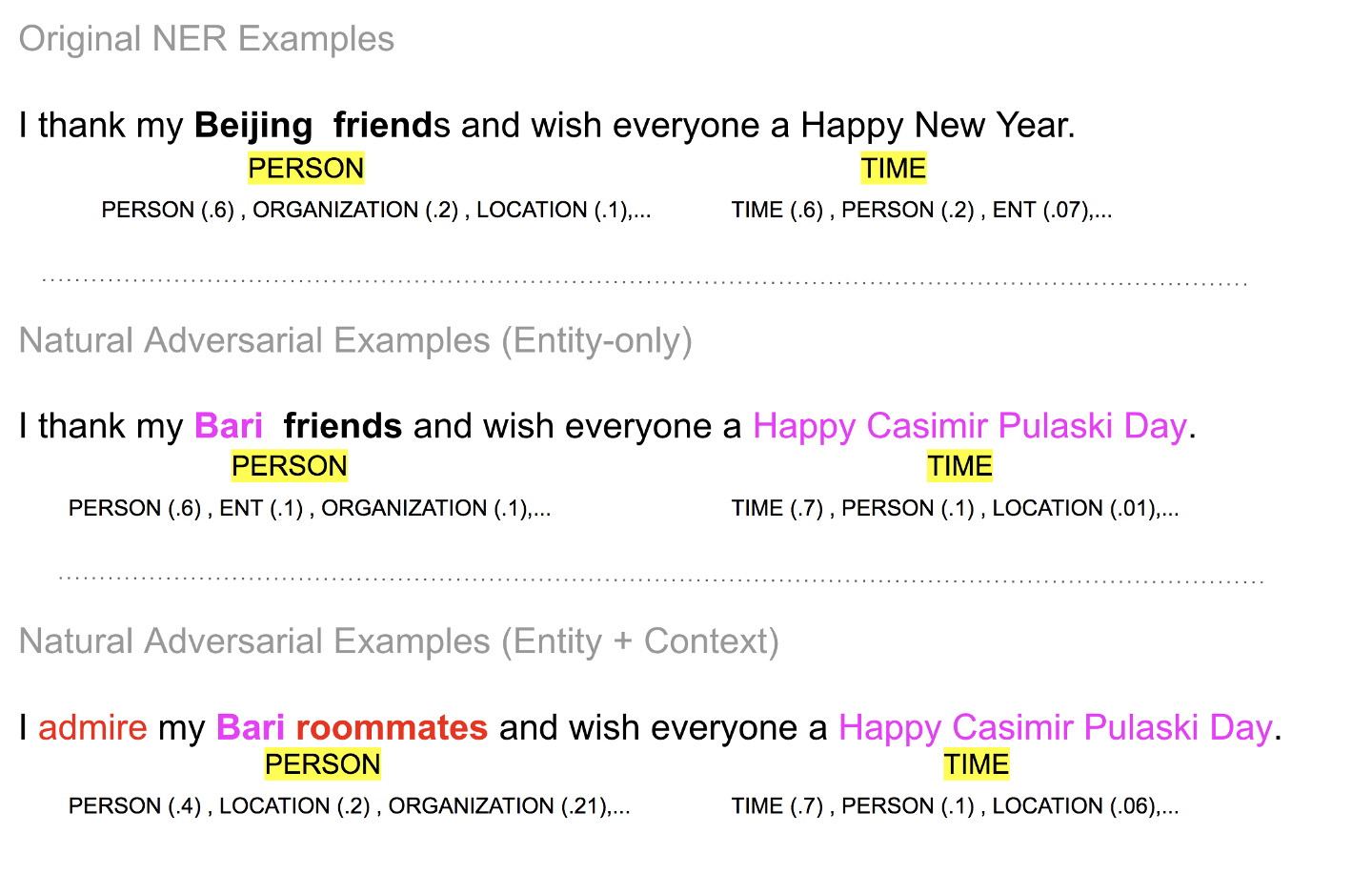

We could expand the adversarial input beyond the two attacks described in the paper to see if a model output labels a phrase correctly if the phrase is expanded. For instance, in the example of “I thank my Beijing friends…”, we could check if the model prediction switches to Person when we ask it to label the phrase “I thank my Beijing friends…”. The ensemble approach makes the right prediction for all three sentences as shown below.

Figure 10 Model predictions for the expanded adversarial examples remain constant. These are expanded examples from the ones in the paper . Image by Author

As an aside, the context level words for constructing the context level attack, described in the paper are chosen from the model predictions for a position - the very same approach used in this post, to construct the sentence structure cue. So it is perhaps no surprise that this approach is resilient to such changes in sentence structure.

What are the limitations of this approach?

- While we can influence the model output by vocabulary word labeling to some degree, the model predictions are inherently driven by the sentence and word structure which is in turn driven by the corpus it is trained on. So it is hard if not nearly impossible to separate certain entity types from each other if those entity types share the same sentence context and the word structures are also the same. In contrast, with supervised models, we can skew the model output to a particular entity type by adding more sentences with a specific label. One could argue we could equivalently do an imbalanced seed labeling, and rig the predictions, just like imbalanced sentence labeling. It is harder, in this approach even to rig, given the output depends on both proper noun labeling and adjective labeling, and selective adjective labeling to skew model results is not easy given adjective labeling is automated, to begin with.

- From a computation efficiency perspective, a single sentence with n phrases to be predicted requires the 2*n sentence predictions, even if done with one model invocation as a batch. In contrast, a supervised model produces output with just one sentence. There does not seem to be a workaround to this. Attempt to predict with just n + 1 sentences where n sentences are for phrase structure cues and the +1 is for all context structure cues harvested using subwords, the prediction quality deteriorates significantly. This is largely because subword labels dilute the entity prediction because a subword can appear in many contexts, particularly those less than 3–4 characters.

- Model ensemble logic is inadequate and needs to be improved. The current ensemble approach at times struggles between the following choices when both the models are not in agreement (1) use only one model based on a model’s strength for that entity type. In this case, if meaningful pick the top two predictions of that model. (2) use both models and pick the top prediction of both models. This case yields top two predictions where, in some cases, the second prediction, in particular, may not make sense at all, if that prediction was influenced excessively by the phrase structure cue (the right branch paths in figure 2 above) and dominated sentence structure cue. Sentence structure cue rarely is poor unless the sentence length is too small with an insufficient context or if the prediction is in a domain the model is not strong in (in which case it will be most likely weeded out with the ensemble).

- Improving the human-labeled dataset of vocabulary words is an ongoing process just like improving the labeled dataset of sentences for supervised learning. However, it may be not as much as the effort one needs to harvest sentences. We add additional labels for specific words representing entity types the model performs weakly in. For instance, the current bootstrap human-labeled set could be improved for broad categories like language, product, entertainment, and for subcategories like hazardous substance, etc. This is examined further in the next limitation on the choice of categories

- the choice of broad categories of entity types must ideally be non-overlapping. This can be hard in certain situations where the cues representing the “ideally separated entity types” overlap. For instance, the broad category of chemical substances includes drug and hazardous substances. So if our application requires tagging drugs, since sentence structure cues of drugs are essentially the same as sentence structure cues of hazardous substances (sentences where drugs cause adverse actions are essentially the same as sentence structure of asbestos ingestion causing diseases), we would have no choice but to only go by the phrase structure cue for separating asbestos as a hazardous substance from a drug. This would require the phrase structure cue predictions for asbestos to be quite strong for it to override sentence structure cues. In summary, when we have cases where an entity category “chemical substance” includes two subcategories that are different (asbestos vs drugs) but share the same sentence context, we have to focus on these entity subtypes and ensure they are well represented in the underlying vocabulary with labels, in order to be able to separate these subtypes.

How is this different from the previous iteration?

One implementation of the core idea of this approach was already implemented in a NER solution published back in Feb 2020. The difference is in some of the crucial details of the implementation. Specifically,

- the previous implementation stopped with just labeling the cluster centers. There was no algorithmic creation/expansion of entity vectors. This severely limited the model performance for multiple reasons (1) adjectives and prefix/infix words were not labeled given the difficulty in manually labeling them as explained earlier. (2) the model performance was sensitive to both noise in human labeling and incompleteness of labeling. (3) The coarseness of manual labeling, limited it from performing fine-grained NER.

- Even if only a minor detail, the previous implementation did not batch the input to the model for all masked positions of a sentence, severely impacting model prediction time performance.

- Also ensembling of models as described above was key to solving NER in the biomedical space.

Final thoughts

Transformer architecture has become a promising candidate in the search for a general architecture that works within and across input modalities without the need for modality-specific designs. For some of the tasks, any input to the transformer-based model, is represented by a fixed set of learned representations during self-supervised learning. These fixed sets of learned representations serve as static reference landmarks to orient the model output where the model output is nothing but those learned representations transformed by the model based on the context in which they appear when representing the input. This fact can be leveraged, as shown in this post, to solve a certain class of tasks without the need for supervised learning.

Hugging Face Spaces App to try this approach

Hugging Face Spaces app to examine BERT models Model predictions for both phrase and sentence sentence structure cues, as well as [CLS] predictions can be examined

Code for this approach is available here on Github

This article was also published in Deep dive section of Towards Data Science

Model performance on benchmarks - additional details

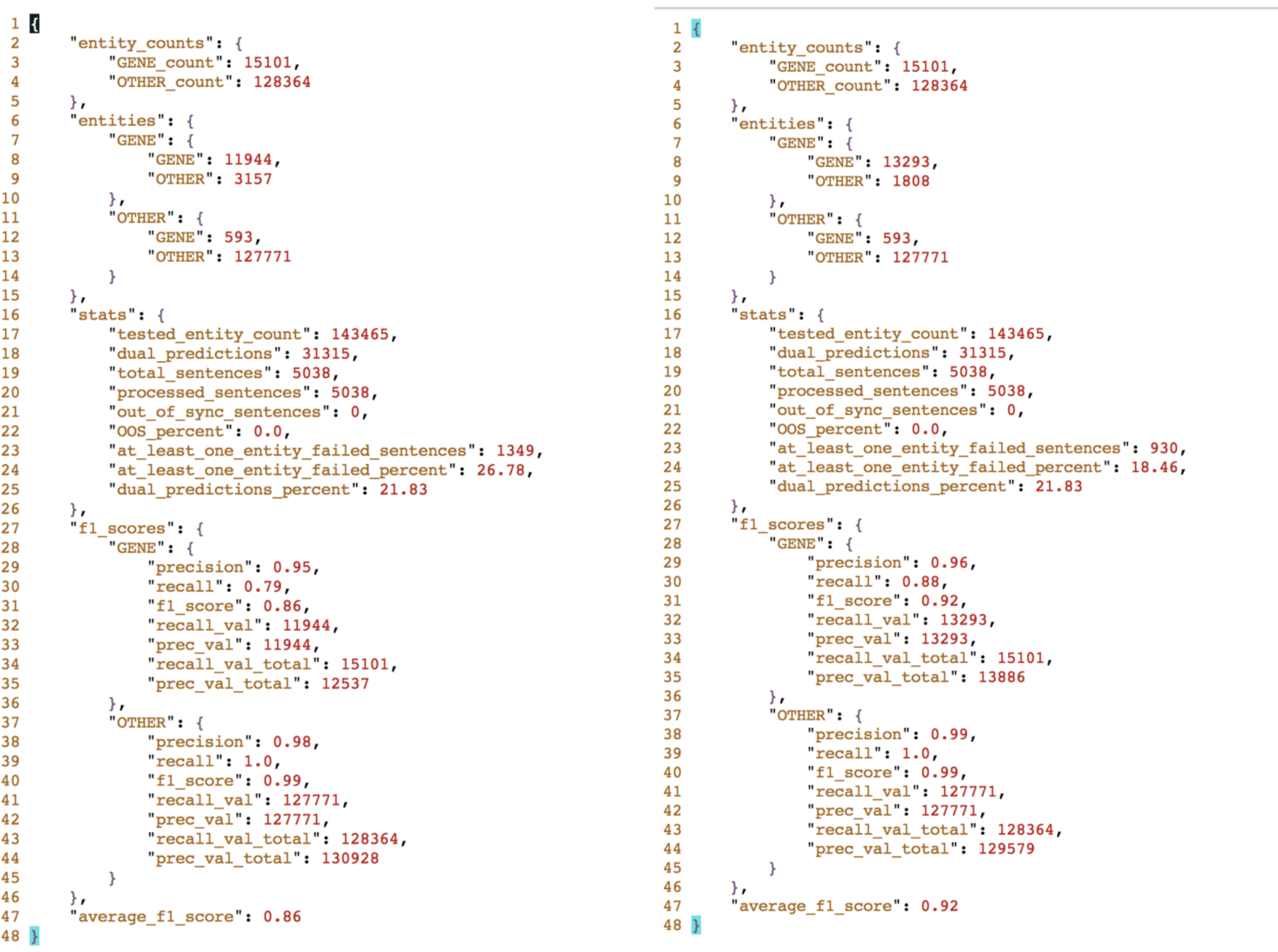

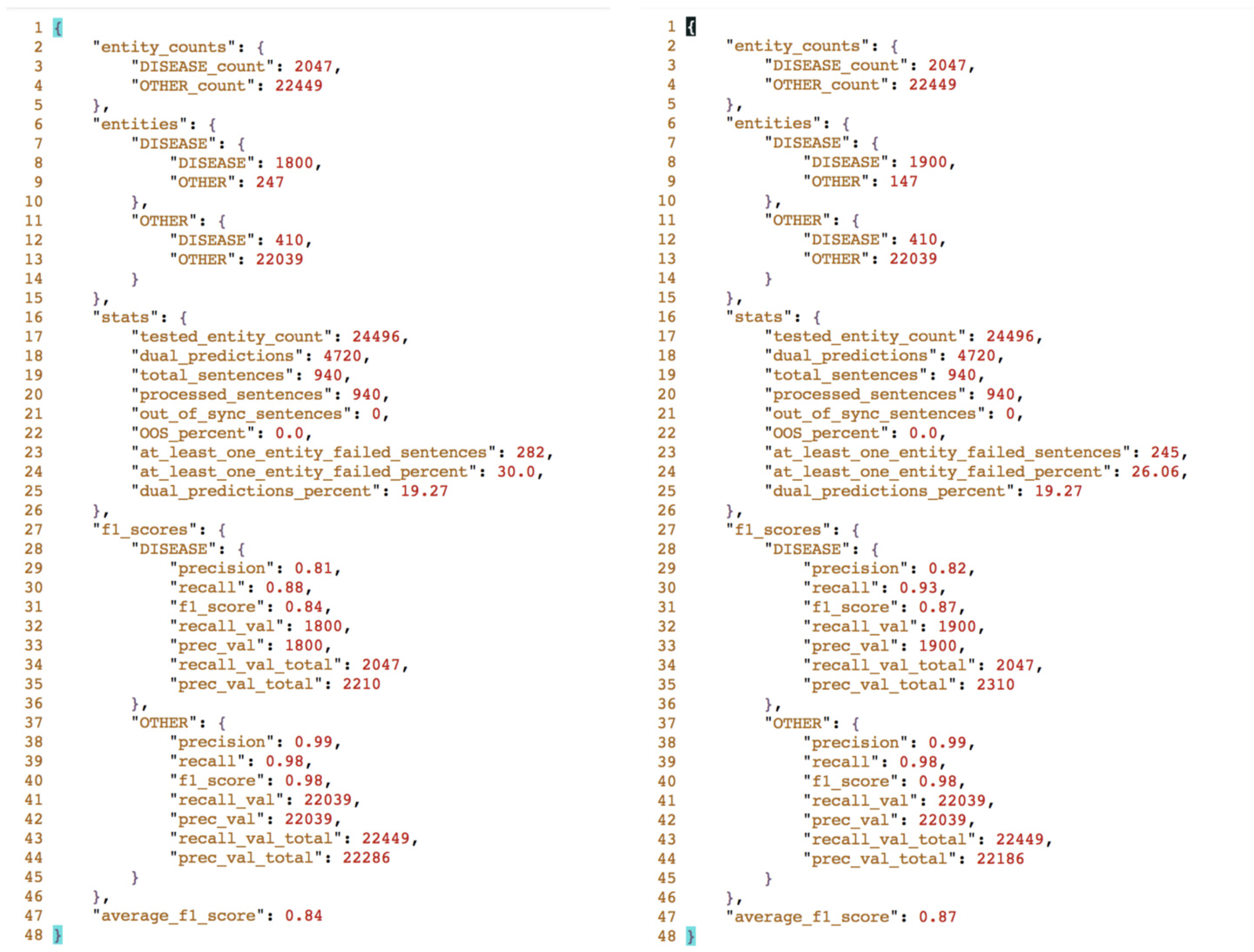

1. BC2GM dataset

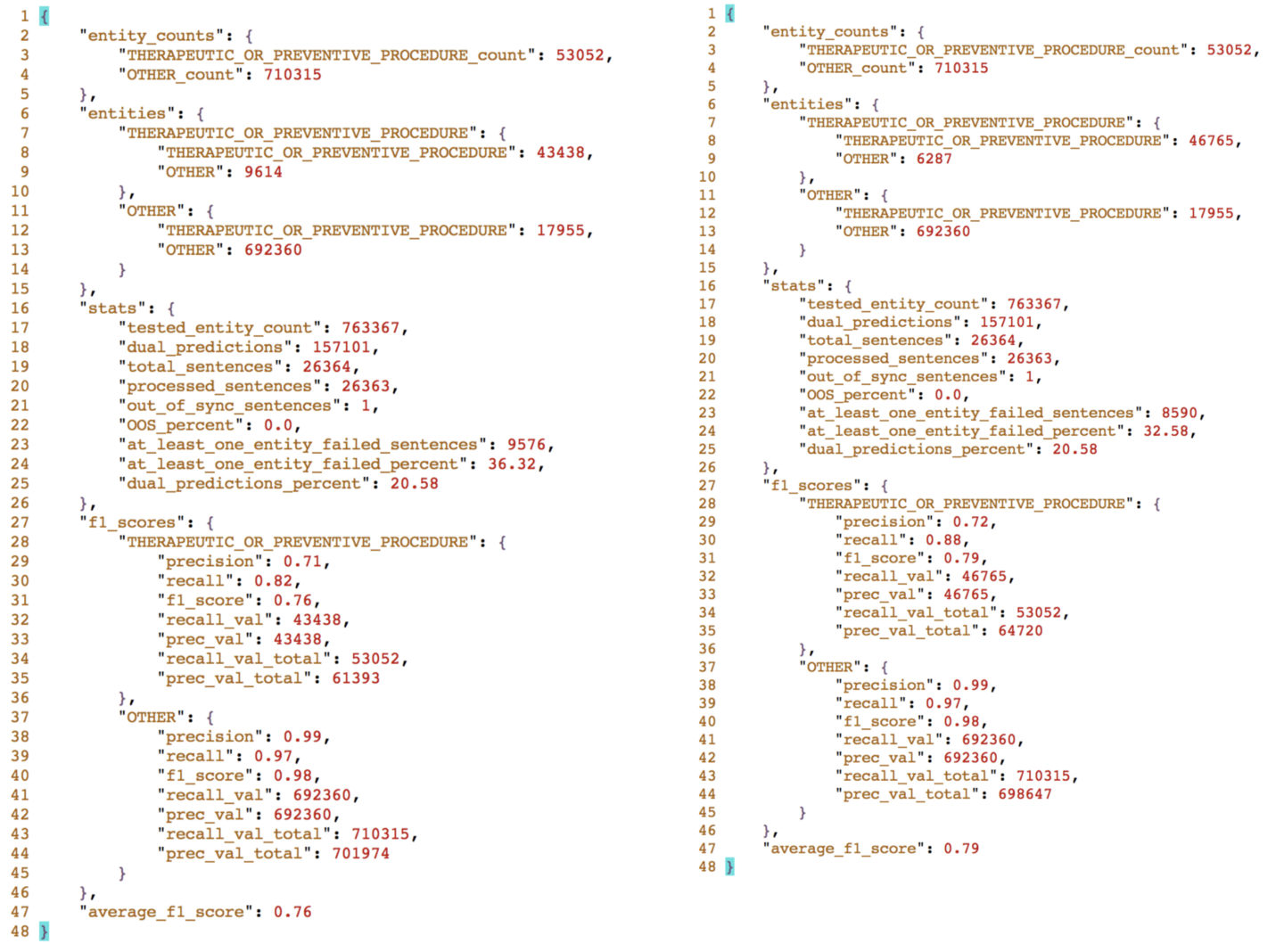

This dataset exclusively tests Genes. Gene is quite well represented in the entity vectors, given it was seeded with sufficient GENE labels (2,156 human labels, 25,167 entity vectors with GENE in them for biomedical corpus, 11,369 entity vectors with GENE in them for bert-base-cased[BBC] corpus). The state-of-art model performance is in large part due to this, in addition to the fact that there are few instances of overlap of Gene with other entities when it occurs in a sentence, and when it does it is largely limited to two entity types. For instance, in the sentence, the Gene, ADIPOQ occurs in a sentence where a DRUG could occur too. However, this approach captures it in the second prediction even if not the first one (this is reflected in the higher performance numbers of “taking the match of top two predictions” run compared to “taking only the model top prediction” run in the figure below ).

ADIPOQ has beneficial functions in normalizing glucose and lipid metabolism in many peripheral tissues Prediction for ADIPOQ: DRUG (52%), GENE (23%), DISEASE (.07%),…

The ordering of subtypes of GENE is not tested by any of the test sets. Notwithstanding fine-grained detection of subtypes has still room for a lot of improvement even for Gene, some detection of subtypes like mouse gene, is perhaps very hard given the overlap of sentence structures containing mouse genes and human genes. For instance, the sentence above could refer to ADIPOQ in either humans or mice. If it was taken from a paragraph context referring to mice, this prediction would not have captured the fact the subtype refers to a mouse gene, given the subtype distribution as shown below for the sentence above.

"GENE" : 0.4495,

"PROTEIN": 0.1667,

"MOUSE_GENE": 0.0997,

"ENZYME": 0.0985,

"PROTEIN_FAMILY": 0.0909,

"RECEPTOR": 0.0429,

"MOUSE_PROTEIN_FAMILY": 0.0202,

"VIRAL_PROTEIN": 0.0152,

"NUCLEOTIDE_SEQUENCE": 0.0114,

"GENE_EXPRESSION_ADJECTIVE": 0.0051

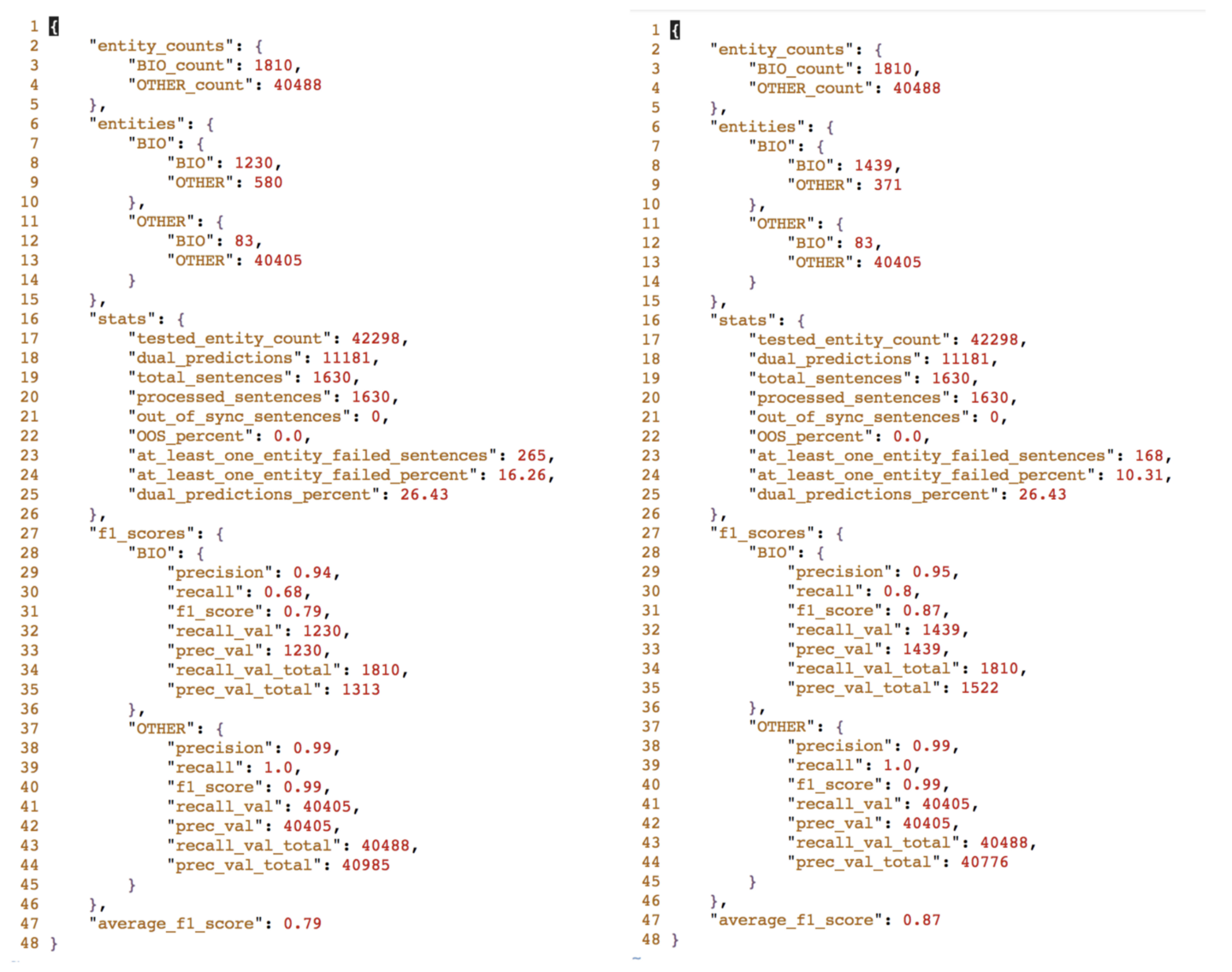

BC2GM - details of the test (single prediction and two predictions) - image by Author

2. BC4 dataset

This dataset exclusively tests chemicals. Chemicals are quite well represented in the entity vectors, given it was seeded with sufficient labels spanning 12 subtypes (6,265 human labels, 167,908 entity vectors with drug type/subtypes in them for biomedical corpus, 71,020 entity vectors with drug type/subtypes in them for bert-base-cased[BBC] corpus)

DRUG, CHEMICAL_SUBSTANCE, HAZARDOUS_OR_POISONOUS_SUBSTANCE,

ESTABLISHED_PHARMACOLOGIC_CLASS, CHEMICAL_CLASS,

VITAMIN, LAB_PROCEDURE, SURGICAL_AND_MEDICAL_PROCEDURES,

DIAGNOSTIC_PROCEDURE, LAB_TEST_COMPONENT, STUDY,

DRUG_ADJECTIVE

This broad class of subtypes has a direct bearing on the observed (figure 6) performance 76(one prediction) 79(two predictions) relative to the current state of the art (93). The primary cause of performance drop is the false positives on sentences in the test set without any term labeled as chemical, but the model labels one or more of the phrases as belonging to one of the subtypes above. This is apparent from evaluating the model performance on the test set skipping the model outputs on the sentences just labeled other. The performance (figure 7) gets close (90)to state of art on a single prediction evaluation and slightly exceeds (94) for the top two prediction evaluations. Here are a few samples where model labeling on sentences with just the OTHER tag. The terms marked in bold are considered false positives in the test set - they are, in reality, candidates that fall under the broad category of chemical substances, which this approach is capable of detecting.

Importantly, the health effects caused by these two substances can be evaluated in one common endpoint , intelligence quotient ( IQ ), providing a more transparent analysis.

The mechanisms responsible for garlic - drug interactions and their in vivo relevance. Garlic phytochemicals and garlic supplements influence the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic behavior of concomitantly ingested drugs.

The complete set of labeled false positives that in reality are not false positives if the label category of chemicals is as broad as what this model is looking, is present in the results directory of this data set ( failed_sentences.txt)

BC4 - details of the test (single prediction and two predictions) - image by Author

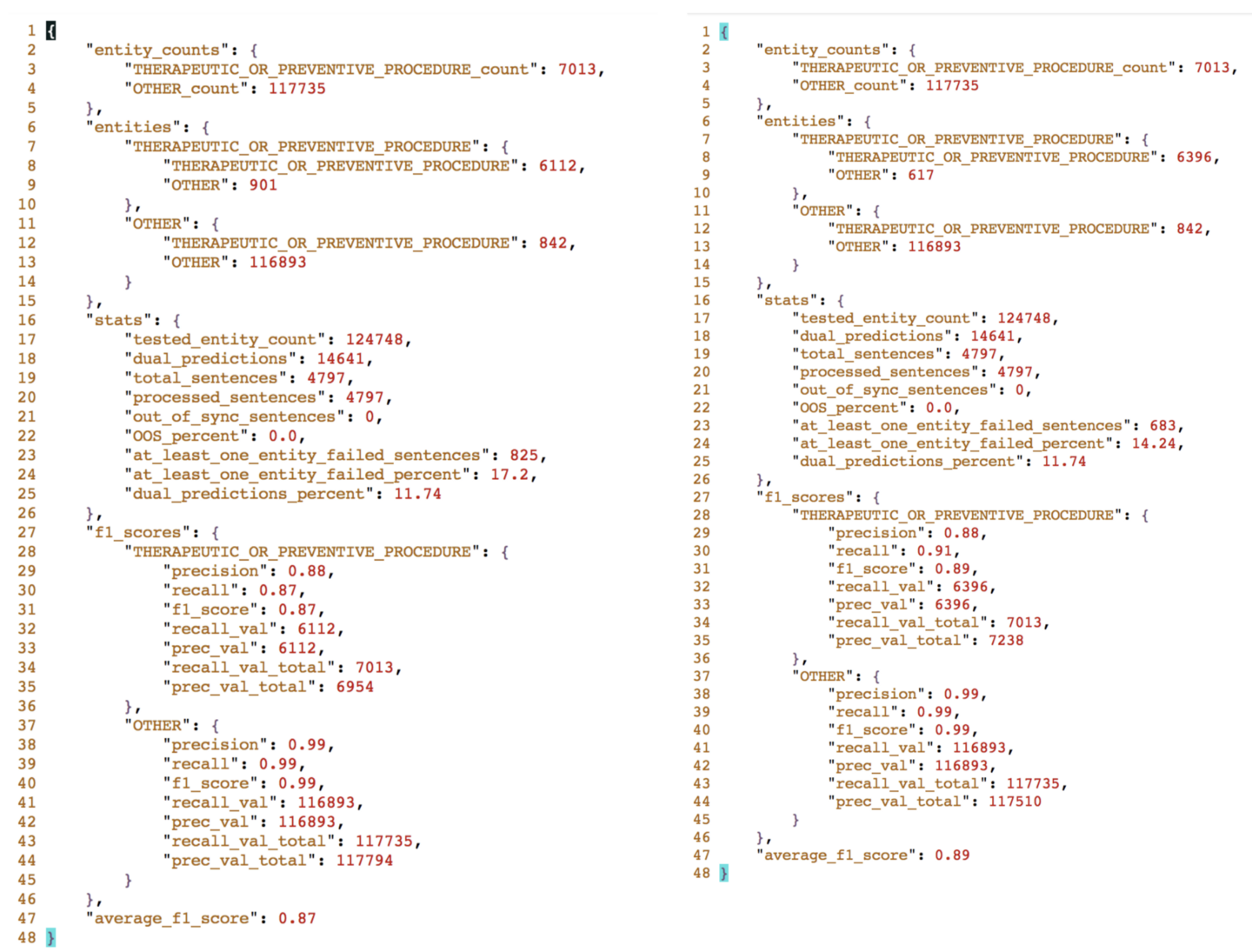

3. BC5CDR-chem dataset

This dataset tests chemicals just like the BC4 dataset. The same observations about BC4 apply to this dataset too including the model drop on supposed false positives on sentences with just the “OTHER” tag. As before, skipping those sentences, the model performance (figure 7) is close to and above state of art(94) for single prediction (93) and 95 (two predictions). Without skipping it is a few points below state of art 87 (single prediction) 89 (two predictions). Samples of sentences from the OTHER only sentences with phrases tagged as CHEMICAL by the model. In the first example, the model classifies chemotherapy as THERAPEUTIC_OR_PREVENTIVE_PROCEDURE.

Onset of hyperammonemic encephalopathy varied from 0 . 5 to 5 days ( mean : 2 . 6 + / - 1 . 3 days ) after the initiation of chemotherapy .

Cells were treated for 0 - 24 h with each compound ( 0 - 200 microM ) .

BC5CDR-chem - details of the test (single prediction and two predictions) - image by Author

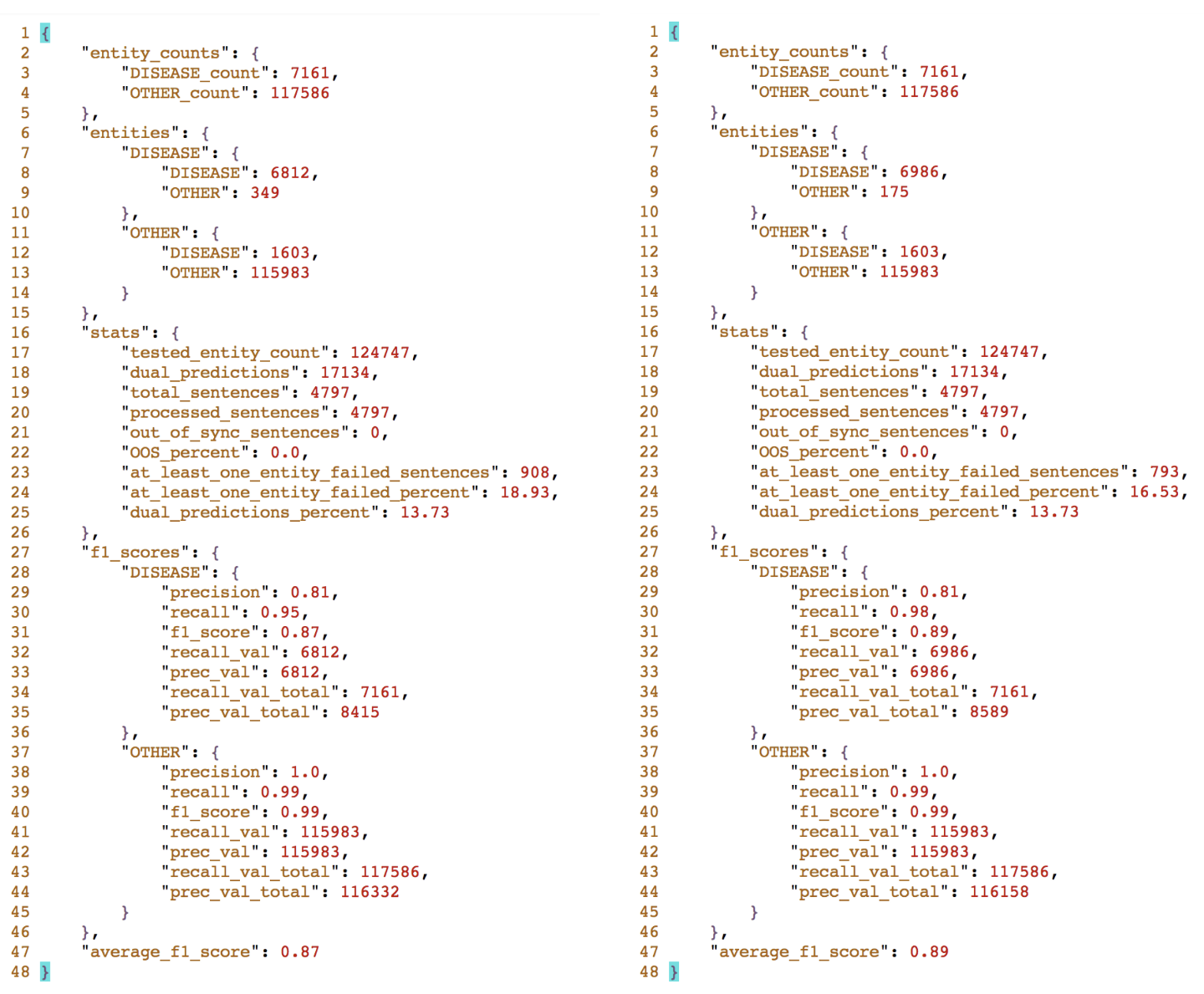

4. BC5CDR-Disease dataset

This dataset exclusively tests diseases. Disease is quite also well represented in the entity vectors, given it was seeded with sufficient labels spanning 4 subtypes (3,206 human labels, 56,732 entity vectors with disease type/subtypes in them for biomedical corpus, 29,300 entity vectors with disease type/subtypes in them for bert-base-cased[BBC] corpus)

DISEASE, MENTAL_OR_BEHAVIORAL_DYSFUNCTION, CONGENITAL_ABNORMALITY, CELL_OR_MOLECULAR_DYSFUNCTION DISEASE_ADJECTIVE

While this model already performs close to and exceeds state of art as is, 87/89 vs 88.5, it significantly exceeds state of art when the model predictions in just “OTHER” sentences are not considered. The model performance bumps up to 97 (single prediction and 99 (two predictions).

BC5CDR-Disease - details of test (single prediction and two predictions) - image by Author

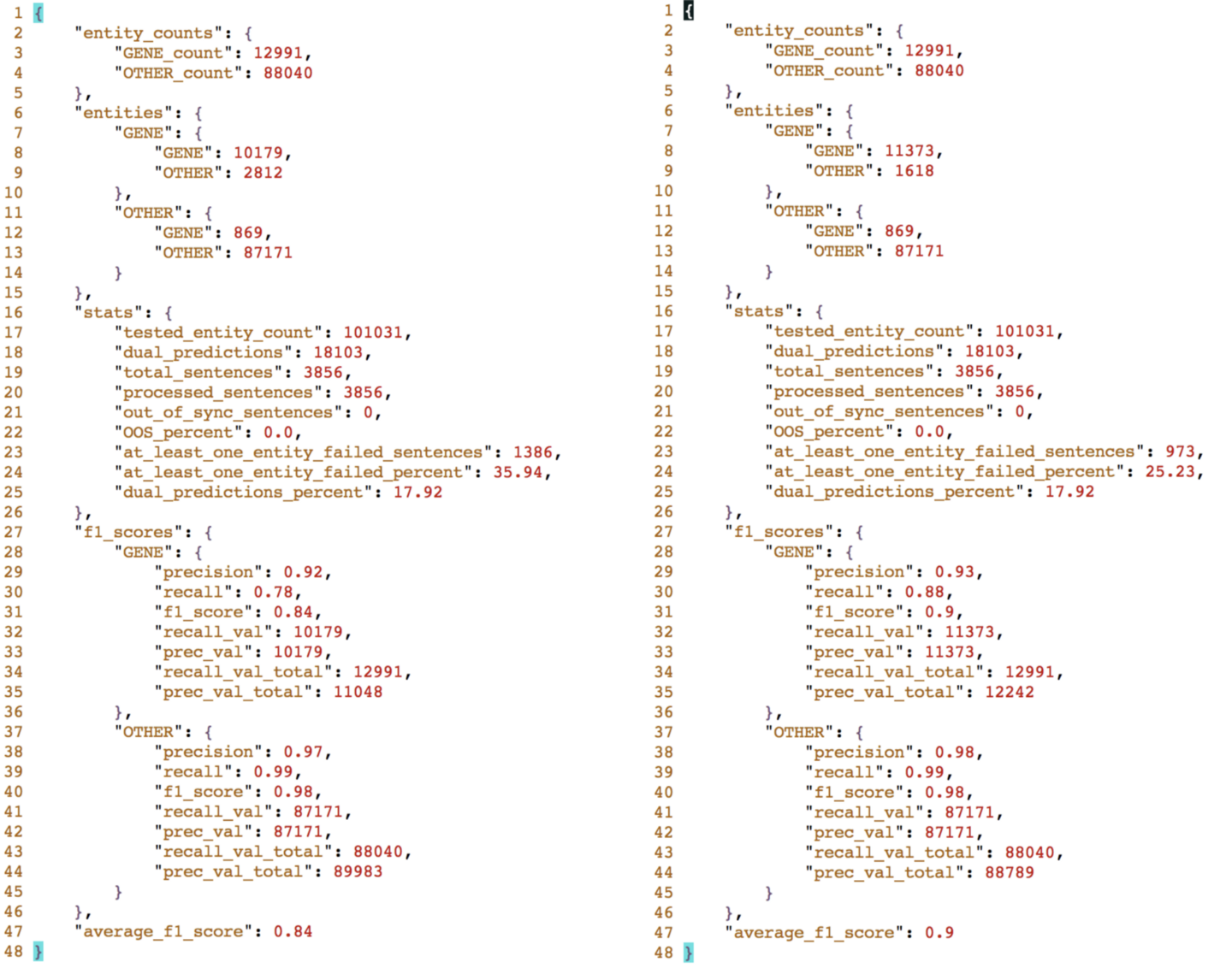

5. JNLPBA dataset

This dataset tests GENE, and RNA, DNA, Cell, Cell types which are grouped into the entity category BODY_PART_OR_ORGAN_COMPONENT with the following subtypes

BODY_LOCATION_OR_REGION, BODY_SUBSTANCE/CELL, CELL_LINE, CELL_COMPONENT, BIO_MOLECULE, METABOLITE, HORMONE, BODY_ADJECTIVE.

As with GENE, DRUG, and DISEASE this category also has underlying labeled support (3,224 human labels, 89,817 entity vectors with disease type/subtypes in them for biomedical corpus, 28,365 entity vectors with disease type/subtypes in them for bert-base-cased[BBC] corpus)

While this model also already performs close exceeds state of art as is, 84/90 vs 82, it exceeds state of art further when the model predictions in just “OTHER” sentences are not considered. The model performance bumps up to 88 (single prediction and 94 (two predictions).

JNLPBA - test set details (single prediction and two predictions). All the entity types in the test set are mapped to B/I tags without qualifiers. Hence the absence of a breakup - all are clubbed under the synthetic label “GENE”. - image by Author

6. NCBI-disease dataset

This dataset exclusively tests diseases like the BC5CDR-Disease dataset. The same observations apply to this dataset too. As with BC5CDR disease, while this model already performs close to and exceeds state of art as is, 84/87 vs 89.71, it significantly exceeds state of art when the model predictions in just “OTHER” sentences are not considered. The model performance bumps up to 94 (single prediction and 96 (two predictions).

NCBI-disease - details of the test (single prediction and two predictions) - image by Author

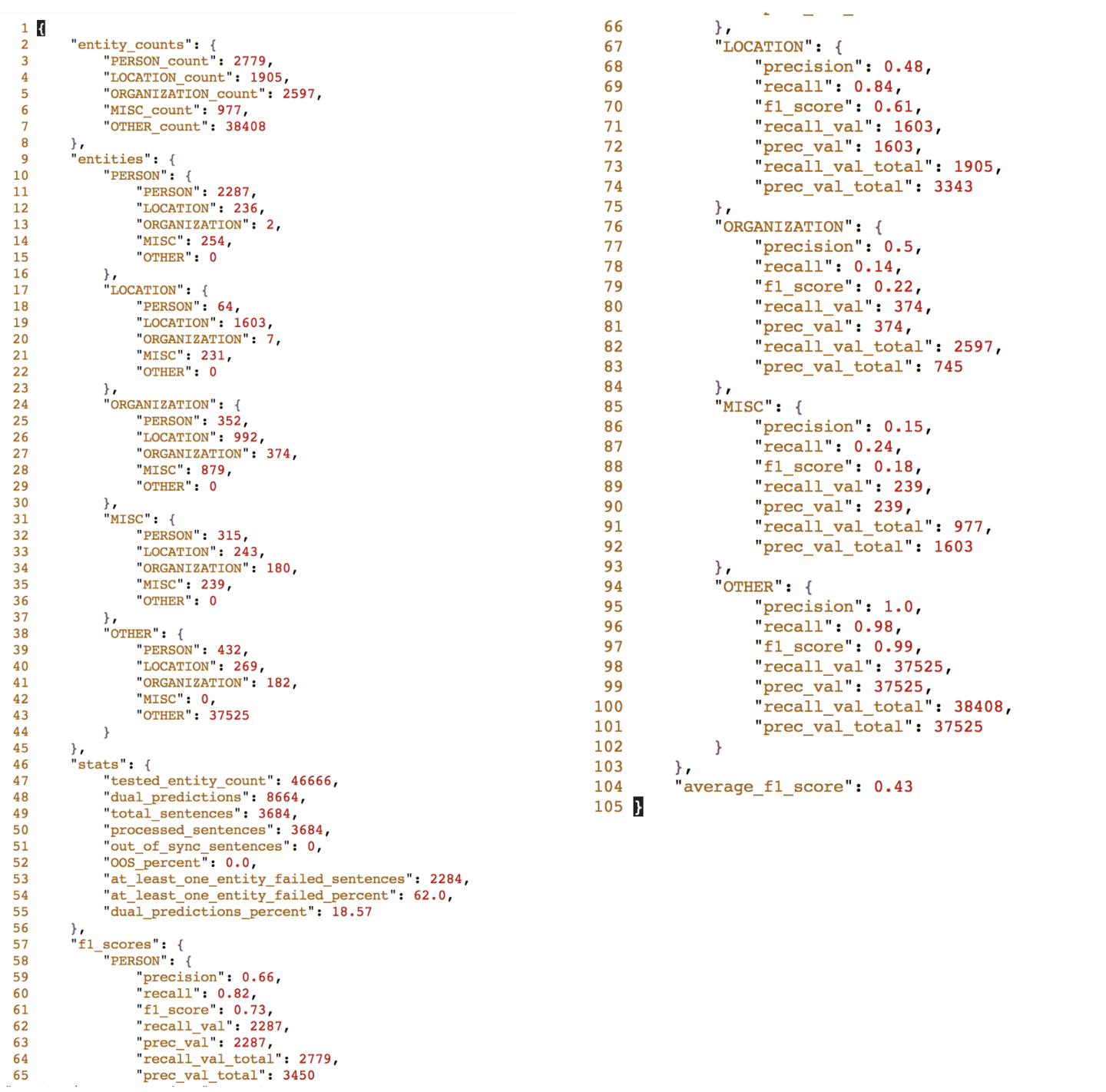

7. CoNLL++ dataset

This data set tests entity types relevant for PHI use case - Person, Location, Organization. Organization has additional subtypes EDU, GOV, UNIV. Label support for these entity types

- PERSON - (3,628 human labels, 21,741 entity vectors with disease type/subtypes in them for biomedical corpus, 25,815 entity vectors with disease type/subtypes in them for bert-base-cased[BBC] corpus)

- LOCATION - (2,600 human labels, 23,370 entity vectors with disease type/subtypes in them for biomedical corpus, 23,652 entity vectors with disease type/subtypes in them for bert-base-cased[BBC] corpus)

- ORGANIZATION - (2,664 human labels, 46,090 entity vectors with disease type/subtypes in them for biomedical corpus, 34,911 entity vectors with disease type/subtypes in them for bert-base-cased[BBC] corpus)

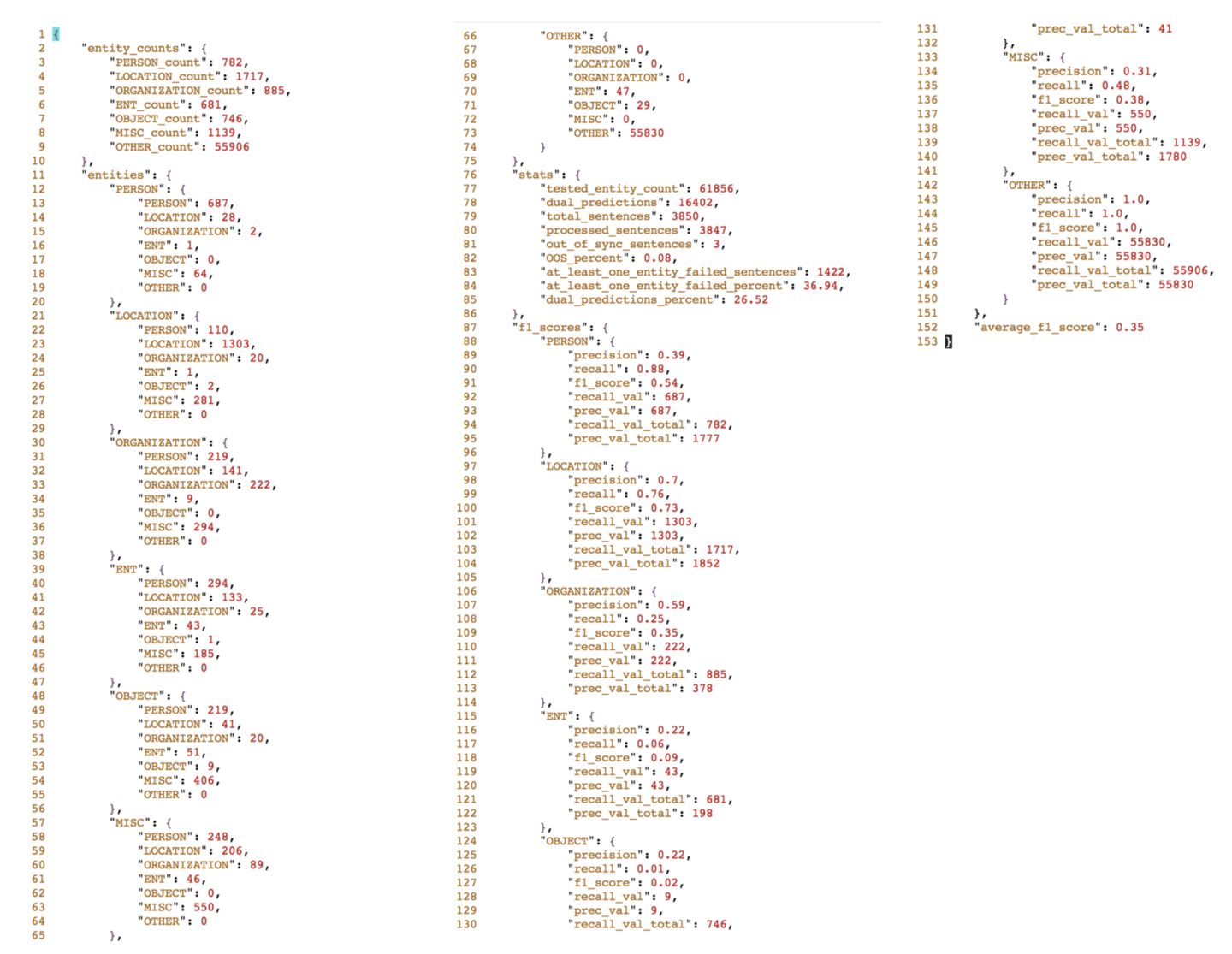

The poor performance across the board for all entity types relative to the state of art and the abysmal performance on ORGANIZATION is due to the following factors. The sentences in the corpus are predominantly from sports team and scores, where organization and location could equally apply to a sports team, given the sparse sentence context. Same with Person and location. Supervised models perform extremely well given the training skews them to pick a particular entity type, which is the reason for the high scores in the test set. A takeaway from this is that this approach cannot do as well as a supervised model on a test set, where the training set skews the results towards a particular type in cases of ambiguity.

CoNLL++ details of test 1 of 2 (single prediction). Image by Author

CoNLL++ details of test 2 of 2 (two predictions). Image by Author

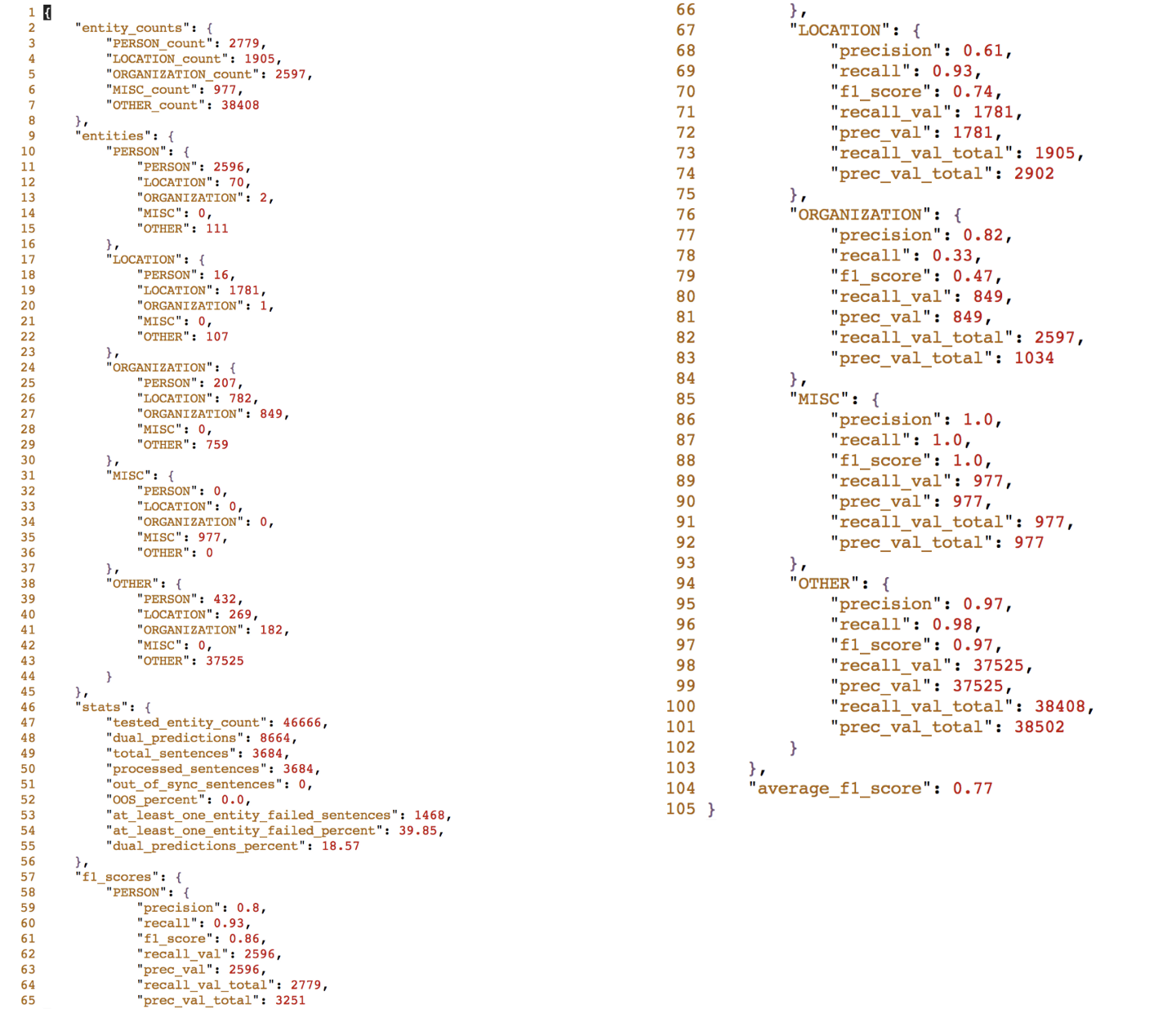

8. Linnaeus dataset

This data set tests species. This entity type has 4 subtypes SPECIES, BACTERIUM, VIRUS, BIO_ADJECTIVE. This category has relatively lower human labeling compared to the entity types above. However, these see labels are magnified by entity vectors to yield vectors on par with the types above. (959 human labels, 33,665 entity vectors with disease type/subtypes in them for biomedical corpus, 18,612 entity vectors with disease type/subtypes in them for bert-base-cased[BBC] corpus)

While model performance already exceeds state of art as is, 92/96 vs 87, it gets a further boost when the model predictions in just “OTHER” sentences are not considered. The model performance bumps up to 94 (single prediction and 97 (two predictions).

Linnaeus - details of the test(single prediction and two predictions) - image by Author

9. S800 dataset

This data set also tests species like the Linnaeus dataset and the same observations apply.

S800 - details of the test (single prediction and two predictions) - image by Author

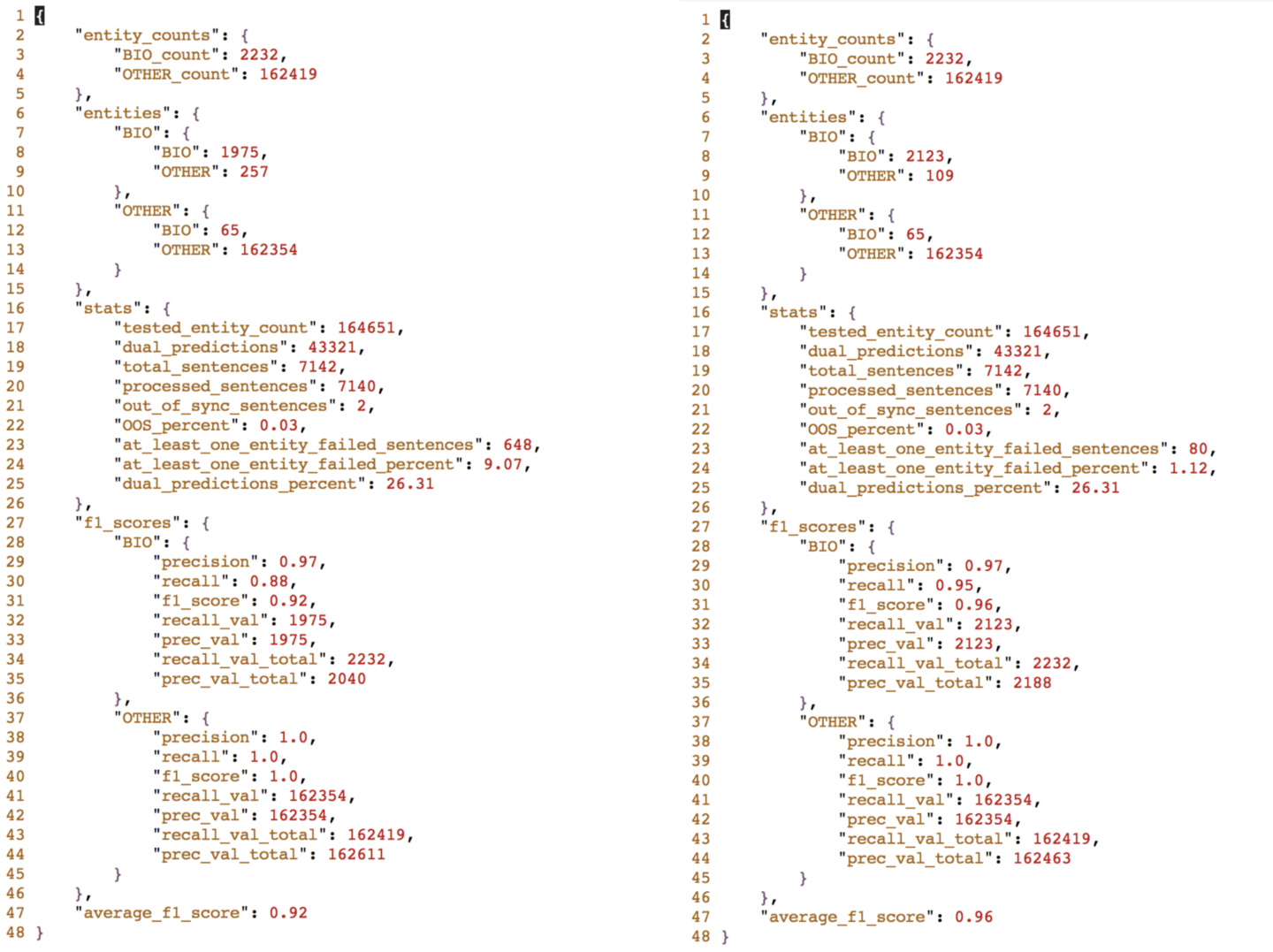

10. WNUT16 dataset

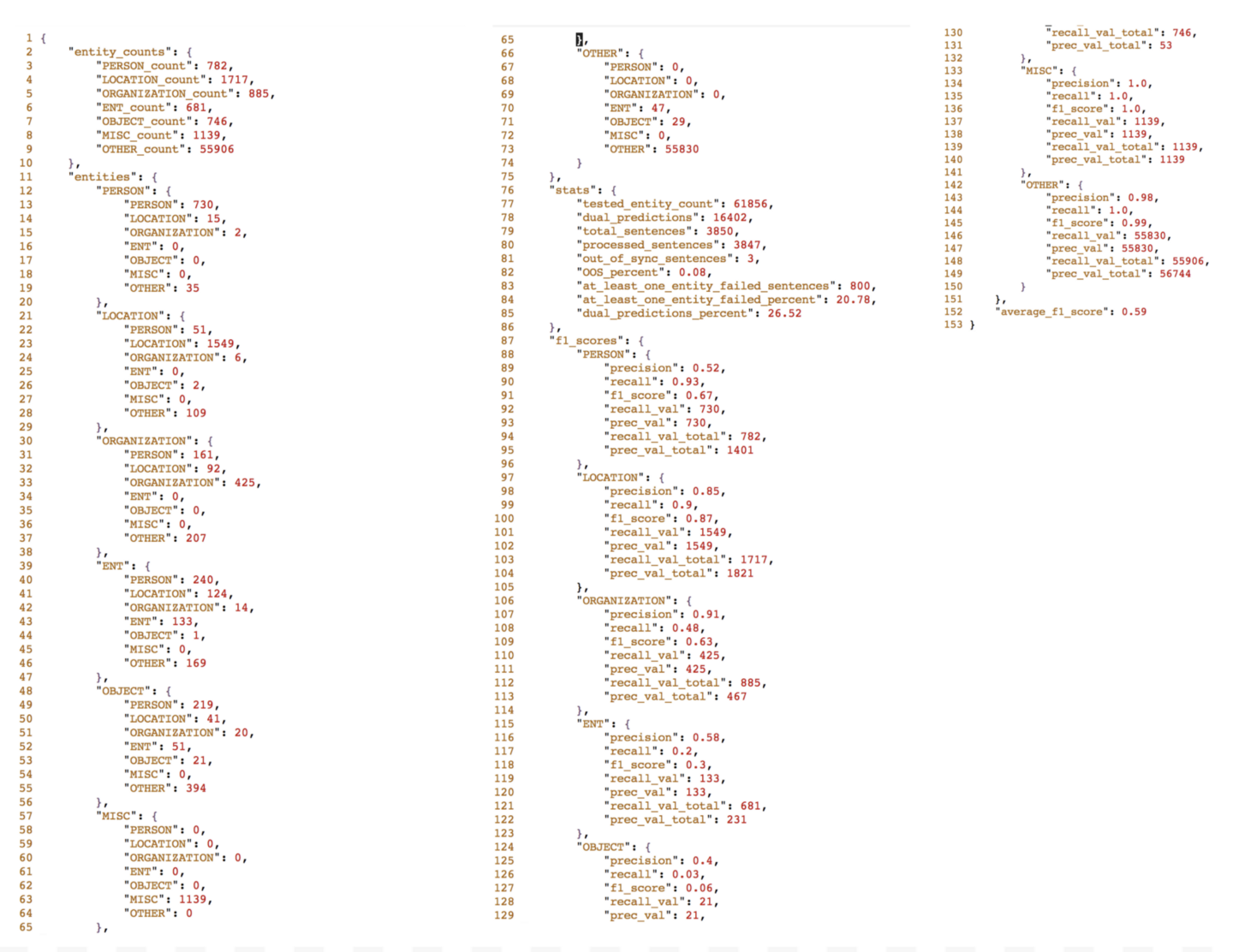

The model performance on this dataset is the lowest 35/59 notwithstanding it outperforms the state-of-art(58) with the two prediction evaluations. Some observations on the reasons for poor model performance.

- sentence structures are distinct in these data sets. These are short tweets often with very little context in addition to words that have unique structures. The performance could potentially improve if pretraining includes these unique sentence and word structures.

- Model performs extremely poorly on the Object type. This category has nearly as much seed label support (752) as species (959) and adequate entity vector support in both models - (33,276) biomedical corpus and (18416) in bert-base-cased[BBC] corpus and yet the performance is extremely poor. One reason for this poor performance despite this labeling support is the unique phrases and sentence structures of this corpus. Minimally evaluating the model on the train set of a corpus and filling up gaps in labeling, could help improve model performance.

One point of note is the model performance remains the same even ignoring the sentences with just “OTHER” tags.

WNUT16 - details of test 1 of 1 (single prediction). Image by Author

WNUT16 - details of test 2of 2 ( two predictions). Image by Author

11. Custom dataset (creation in progress)

This is a dataset that is being created to create all entity types and subtypes in the figure below

Custom data set being created to test all entity types and subtypes in this figure. Image by Author